Will a vaccine give us our old lives back?

Many of us are desperately hoping new and effective coronavirus vaccines will soon transport us back to our pre-Covid lives. But many scientists are warning that their arrival probably won't mean throwing our face masks in the bin anytime soon.

Scroll down ↓ to find out how vaccines work and why they need to reach a huge number of people in order to see an end to our socially distanced lives.

How do vaccines work?

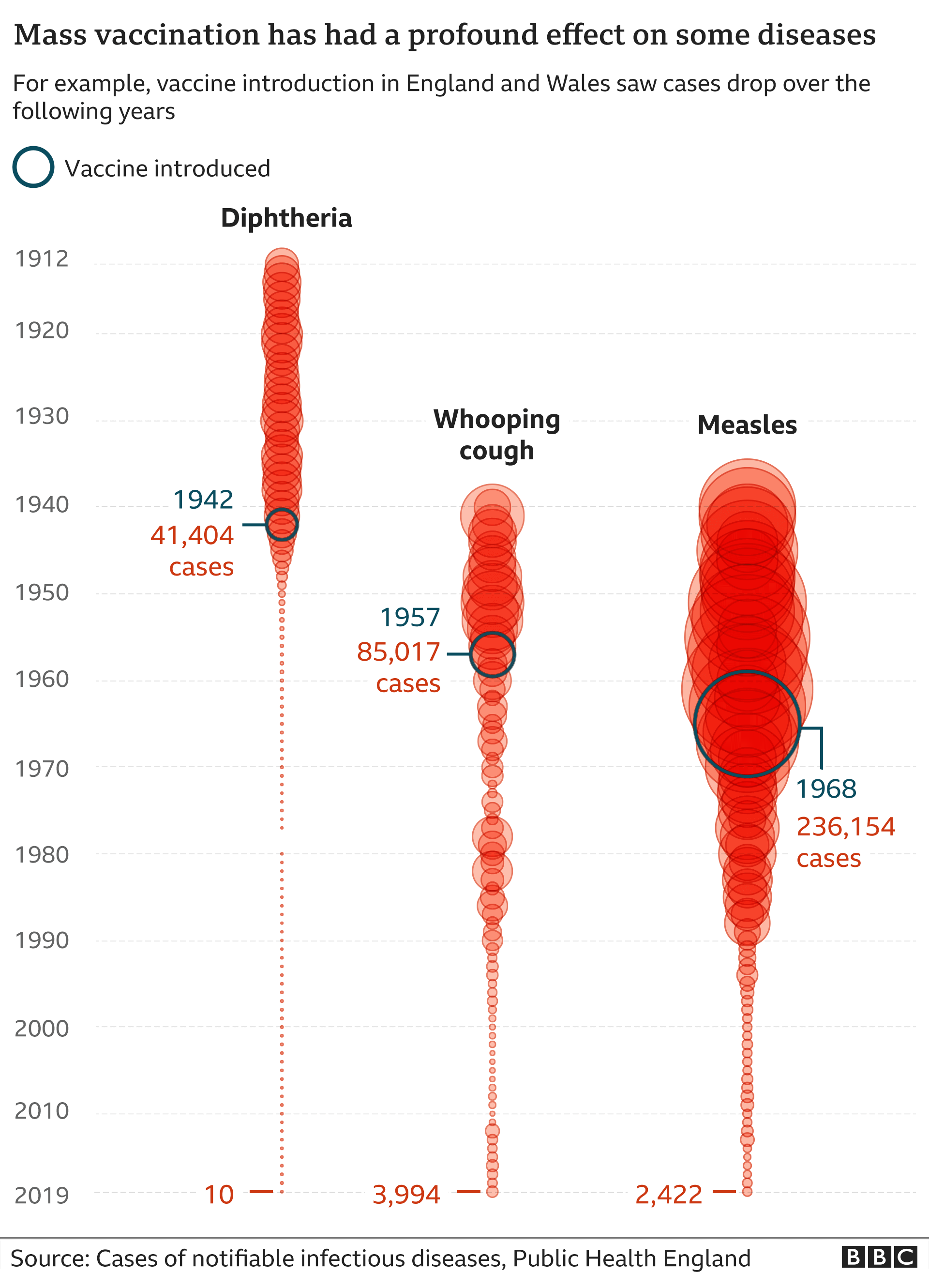

Vaccines are widely considered to be one of the greatest medical achievements of the modern world.

Every year they stop an estimated two to three million deaths, preventing more than 20 life-threatening diseases, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

Childhood illnesses that were common less than a generation ago are increasingly rare. And smallpox - which killed hundreds of millions of people - has been completely eradicated.

But these successes have taken decades to achieve - and many of us are now expecting effective coronavirus vaccines to have similar results in a radically shorter time frame.

News that some of the emerging vaccines are more than 90% effective - meaning about nine in 10 people receiving them would be protected from developing Covid-19 - has led many to believe we could soon be ditching social distancing and throwing away our face masks.

In the US and the UK, where regulatory approval for the jabs is being granted quickly and mass vaccination programmes planned, some have even suggested life could be back to normal by spring.

But many scientists and global health experts are warning that vaccines, with limited initial supplies and roll-out to selected groups, although protecting vulnerable groups and front-line health workers, are unlikely to transport us back to our old way of living anytime soon.

Tedros Ghebreyesus, head of the WHO, has said as much himself.

"A vaccine will complement the other tools we have, not replace them," he said. "A vaccine on its own will not end the pandemic."

View on Twitter

An explanation for this gap in expectations - between the optimism of some politicians and the public on the one hand and the hesitancy of many science professionals on the other - could be, partly, down to a lack of appreciation of how big a task it is to get enough vaccine to enough people.

What many of us may not realise is that when we are talking about infectious diseases - those that pass from person to person - to truly protect everyone, we need to inoculate in very large numbers.

This is because the power of a vaccine is not just in its ability to protect us as individuals, it is in its capacity to protect the people around us and the communities in which we live.

Take Shona, here, for example.

How vaccines protect us - and others

The problem for Shona, us and our communities is that no vaccine is ever 100% effective.

The measles vaccine is one of the best and protects 95%-98% of people.

The Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna Covid-19 vaccines and their 90%+ efficacy also fall short and we don't yet know whether that percentage will drop over time or outside clinical trial conditions.

This means about one in 10 people would not be protected against Covid-19 - even if we vaccinated everyone. Without 100% coverage, which is unlikely in any vaccination programme, the number of people at risk would be higher.

They could be among the most vulnerable - we already know older people tend to have a weaker response to vaccination, although the coronavirus vaccines have shown encouraging results in this regard.

If you just protect the vulnerable, you will stop deaths that are happening in the vulnerable and you will reduce the burden of hospital cases, but it won't stop transmission Prof David Salisbury, former director of immunisation at the UK Department of Health

On top of this, some people in our communities, for health reasons, such as those undergoing some forms of cancer treatment, may not be able to get vaccinated at all.

This means a significant pool of people around us will always be left at risk. Some of our friends and family may be among them.

But there is still a way of ensuring we indirectly protect everyone - and that is to harness the power of mass vaccination.

If we vaccinate enough people within our community an incredible thing happens. We create multiple invisible shields that disrupt a germ's chain of transmission, indirectly protecting our vulnerable friends and family.

This is sometimes referred to as population protection or herd immunity.

Here's how it works.

How vaccinating lots of people protects the vulnerable

So how many of us will need to have the coronavirus vaccine?

What we do not yet know - and this is crucial to reaching herd protection levels - is how far the current Covid-19 vaccine contenders are able to prevent transmission, or offer sterilising immunity.

We may have to wait some time to know this for sure, but the scientist behind the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine suggests there is a chance that at least one of them could help reduce the risk.

But even if we assume they do help block transmission, the number of people who would need to receive the vaccine in order to fully protect the vulnerable is high.

This is because even with significant levels of inoculation with an effective vaccine, a large number of people are still left exposed, says Prof David Salisbury, a former director of immunisation at the UK Department of Health and associate fellow at the Chatham House think tank.

And this is down to some simple maths, he explains.

Why people are left unprotected - even with significant vaccination levels

This is why scientists are pointing out that until we have enough vaccine to go beyond vaccinating at risk groups against Covid-19 and reach a large proportion of the population, we won't see an end to social distancing.

"If you just protect the vulnerable, you will stop deaths that are happening in the vulnerable and you will reduce the burden of hospital cases, but it won't stop transmission," says Prof Salisbury.

Transmission will continue between people who haven't been vaccinated, who can then spread it to unvaccinated vulnerable people and vulnerable people who have been vaccinated but have not made a protective immune response, he says.

[A vaccine] will end the pandemic, it is just a question of when, and that's the hardest bit to anticipate because getting this vaccine out that is the biggest challenge Prof Azra Ghani, an epidemiologist at Imperial College London

This inevitably means that in order to avoid pockets of transmission developing and exposing vulnerable friends and family within our communities, we need to achieve high levels of vaccination across all ages in all geographical areas.

Given how interconnected the world is in terms of movement of people and trade, this also means doing the same in every country across the world.

"This is a global pandemic, this isn't a national epidemic, so you've got to stop the virus everywhere and, until you do, nowhere remains safe," says Prof Salisbury.

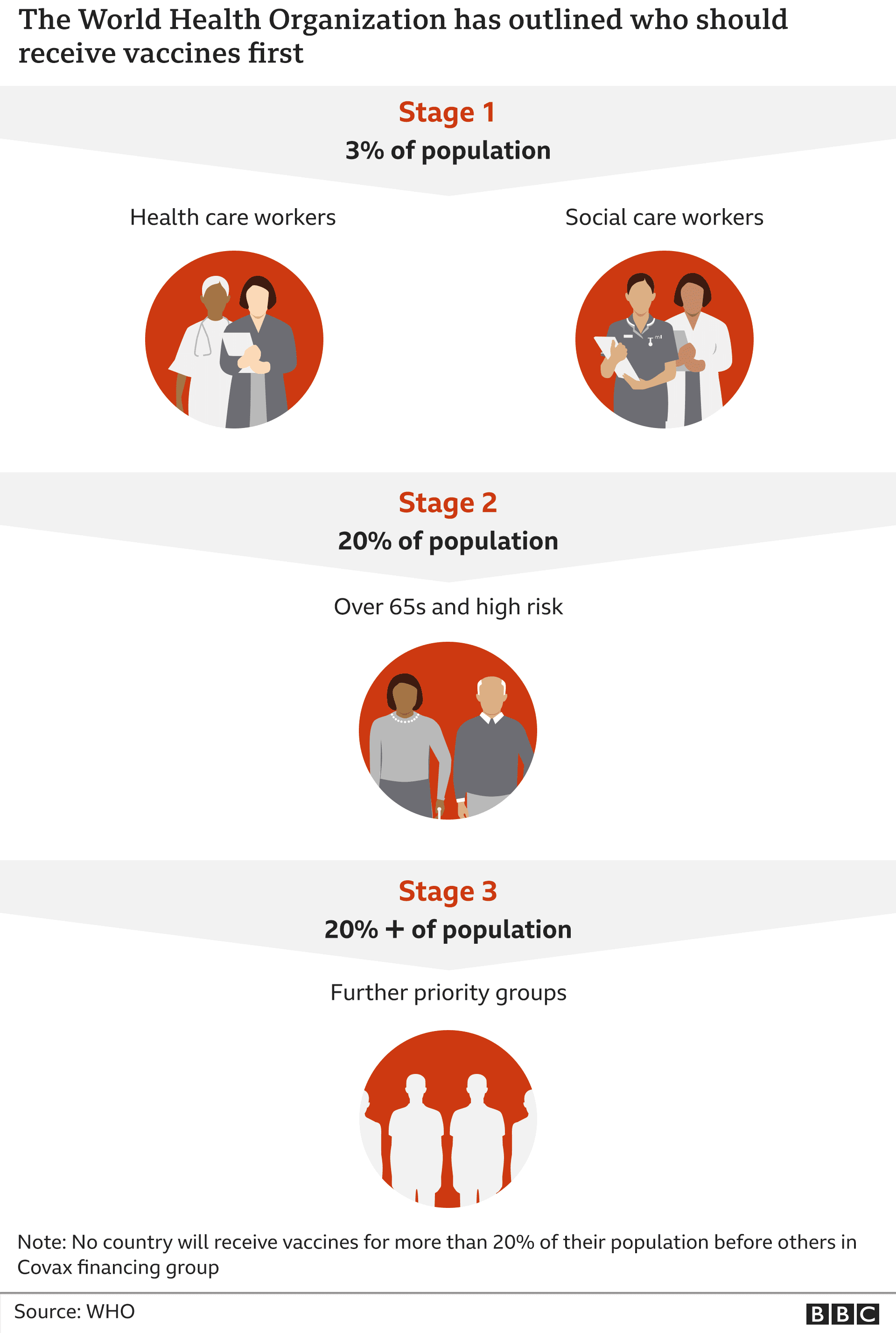

Currently the global plan for roll-out means those most at risk and healthcare workers will receive the limited number of available vaccine doses first.

But some countries have already indicated they plan to vaccinate beyond at-risk groups when supplies allow, including the US and the UK.

The head of the UK's National Health Service (NHS) has said it could take until April for all those most at-risk to receive doses - but the government's eventual aim is to vaccinate as many people over the age of 16 as possible.

Overall, the WHO estimates that between 65% and 70% of people will need to be immune before transmission is interrupted, herd protection achieved and everyone and everywhere declared safe.

Prof Azra Ghani, an epidemiologist at Imperial College London who specialises in the mathematical modelling of infectious diseases, thinks we need to reach 70% to be "on the safe side".

She believes achieving this will, ultimately, return our lives to normal, but getting there will be a difficult process, even without any unforeseen obstacles.

"It will end the pandemic, it is just a question of when, and that's the hardest bit to anticipate because getting this vaccine out that is the biggest challenge."

So, how do you vaccinate billions of people?

Immunising a large chunk of the UK's 68 million people will be an immense task, never mind reaching most of the globe's 7.8 billion residents.

Nothing on this scale has ever been attempted before.

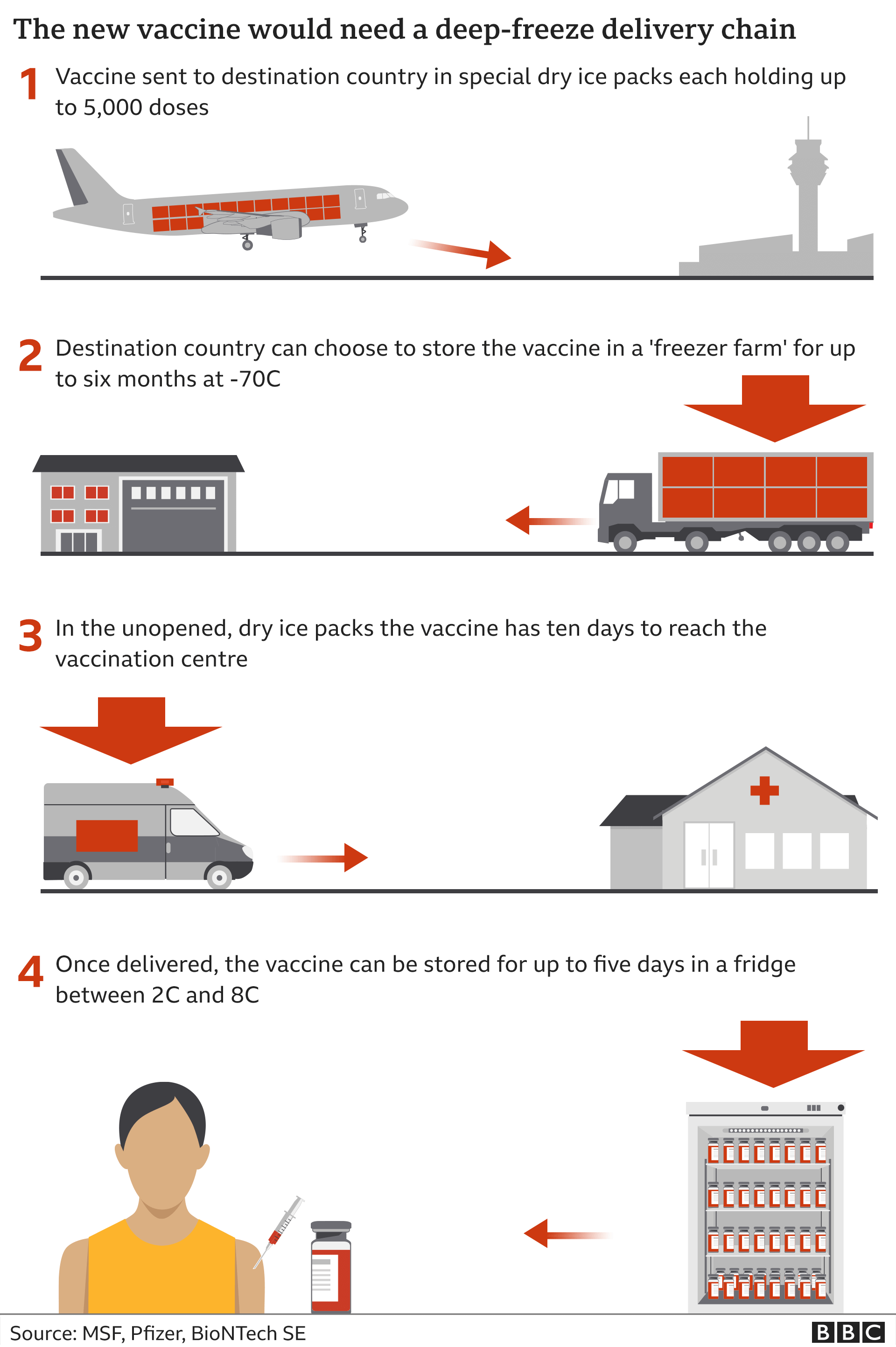

The vaccines and their equipment - such as the vials to house them - need to be manufactured in mass quantities. Vaccine supply may not be able to meet demand for some time.

The vaccines then need to be transported from factories and delivered to health centres - including those in isolated, hard-to-reach communities across the world.

Some of the vaccines are also likely to require cold storage, for example the Pfizer vaccine needs to be kept at temperatures of -70C (-94F).

The UK's NHS is setting up a network of vaccination centres to manage the logistical task after the country became the first in the world to approve the Pfizer jab as well as one made by Oxford University and AstraZeneca.

But for others the challenge will be greater.

German logistics giant Deutsche Post DHL has warned that large parts of Africa, Asia and South America have insufficient cooling facilities in the "last mile" delivery stages as well as not enough storage, which would "pose the biggest challenge" to delivering a vaccine at scale.

Winning over populations

And there is yet another barrier that could slow the task of reaching enough people to protect the vulnerable.

Health officials will have to overcome a rising tide of "vaccine hesitancy" - growing numbers of people who are reluctant to have inoculations - a phenomenon regarded as one of the top 10 threats to global health by the WHO.

In the UK, about 36% of people said they were either uncertain or very unlikely to agree to be vaccinated, a report by scientific institutions the British Academy and the Royal Society found.

Similar figures were recorded by a YouGov poll in November.

This vaccine hesitancy, along with the growth of misinformation around vaccination - the so-called anti-vax movement - could make herd protection by vaccination harder to attain in many countries.

Prof Ghani suggests reassuring people who would normally get vaccinated but who are currently feeling "a little bit nervous" about how quickly Covid-19 vaccines have been developed, will be crucial to mass roll-out in the UK.

The task of winning over populations and getting people to turn up for appointments may mean we move towards herd protection levels "at a slower timescale", she says.

So can a vaccine actually bring back normal?

Despite the scientific and practical challenges of delivering an effective vaccine accross the UK and also the world, the good news is that it looks likely the first-generation vaccines will have a significant impact on the global battle against Covid-19.

In the short term they will help prevent the most vulnerable in our communities from developing severe disease and dying, especially older people with pre-existing conditions and front-line health workers.

Pfizer/BioNTech's announcement that their vaccine appears to protect 94% of adults over 65 years old is an important boost to this work.

The bad news is that it could well take months or possibly years to vaccinate enough of the global population to make the whole interconnected world safe and reach a point where we can all return to full normal.

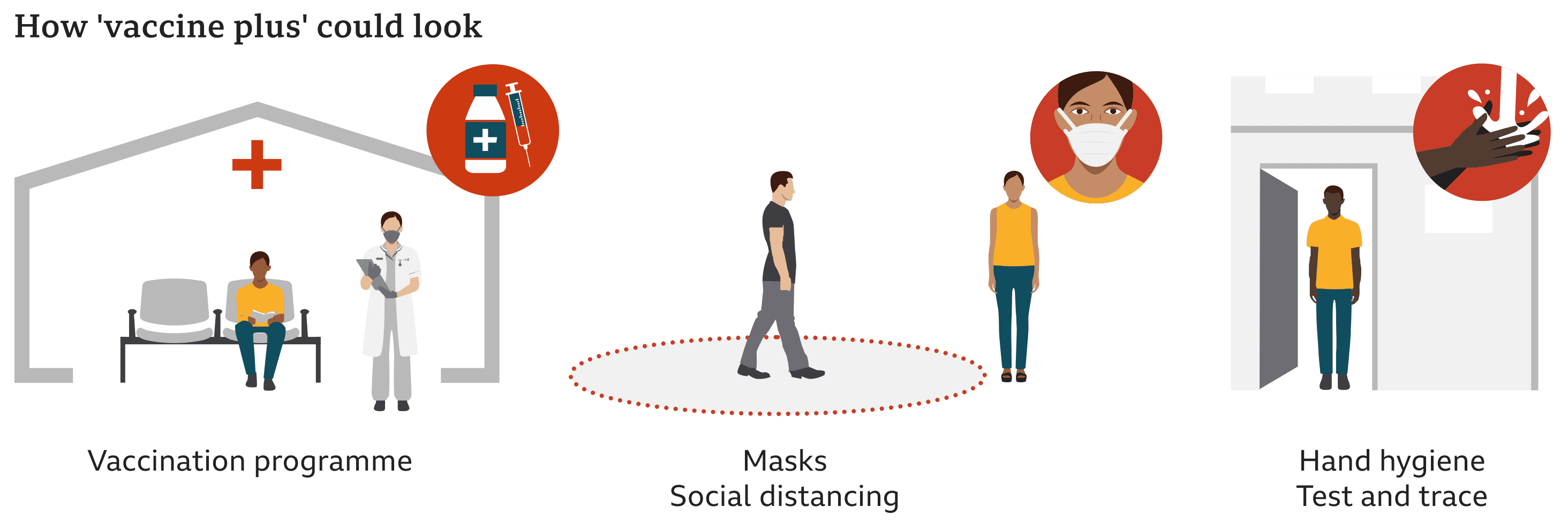

Era of 'vaccine plus'

Suggestions that vaccines will be able to take us back to where we were pre-Covid by Easter have given people an unrealistic expectation, says Prof Salisbury, and such an outcome, in the absence of the interruption of transmission, is "unlikely".

Even countries with strong health infrastructure and experience of mass vaccination programmes - like the UK - will find reaching enough people to break the chain of transmission a challenge, he says.

While the outlook for at-risk groups will be "undoubtedly brighter" in 2021, Prof Salisbury says, the rest of us look likely to be taking extra measures for some time to come, something he refers to as "vaccine plus".

Prof Ghani agrees and estimates it will take two more years to "to get the whole world back to normal", but with the process likely to be quicker for high-income countries like the UK.

But she warns that while vaccines will ultimately end the pandemic, they will not "get rid of the virus" and the world will need to "keep vaccinating" just as it does with other diseases.

So with a new era of "vaccine plus" possibly now dawning in the battle against Covid-19, 2021 is likely to require us to continue to dig deep for a number of months to come - and possibly beyond.

How do pandemics end?

How do pandemics end?

This is what coronavirus will do to our offices and homes

This is what coronavirus will do to our offices and homes

Global outbreak tracker

Global outbreak tracker