Channel migrants tragedy: Terrifying final hours of their fatal journey

In the freezing waters of the English Channel, a group of men, women and children are treading water and holding each other’s hands to stay afloat.

Some are making desperate calls to rescuers on mobile phones held above the waves. But, as hypothermia sets in, their devices slip from their hands before they can send their location.

The dinghy in which they had hoped to reach British shores has a broken motor and is deflating.

One member of the group manages to send a voice message home.

Just hours later, all but two of at least 30 people are dead - the worst migrant mass drowning in the Channel ever recorded.

What went wrong? Here we piece together the final hours of the group - through survivors’ testimony, mobile phone messages, shipping data and the emergency response.

Tuesday 23 November

Departure

As dusk falls, 22-year-old Hadiya Rzgar Hussein, her seven-year-old sister Hasti, brother Mubin, 16, and mum Kazhal, 46, gather their belongings together at the makeshift camp at Grande-Synthe, where they have been staying for several weeks.

They are tired and scared. French police recently dismantled the Grande-Synthe site, evicted its occupants and destroyed the family’s tent - and they are desperate to reach their relatives in the UK.

To do this, they need to brave the so-called “death route” across the English Channel, paying people-smugglers to get them there on small, cheap inflatable boats.

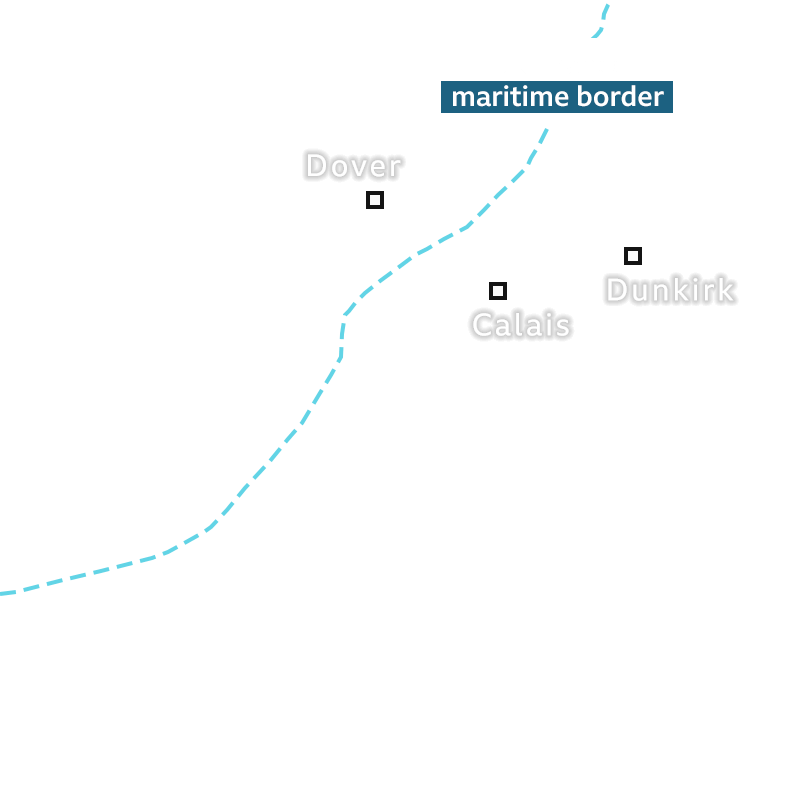

While the white cliffs of Dover are visible from some of this coastline on a clear day, the crossing is fraught with danger. It is one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes and those crossing must navigate freezing air and sea temperatures, and dangerous currents.

Hadiya and her family have already tried to make it across three times before. Once they were turned back by police, once they ran out of fuel and on the third attempt the boat’s engine failed.

But Hadiya’s dreams of becoming a doctor drive her and her family onwards.

“Who doesn't wish for a good life? Who wants a bad life? All four of them wanted to go. I prayed to God, ‘please make their wishes come true’," their father Rizgar Hussien Mohammed tells the BBC from his home in Iraqi Kurdistan.

18:00 French time

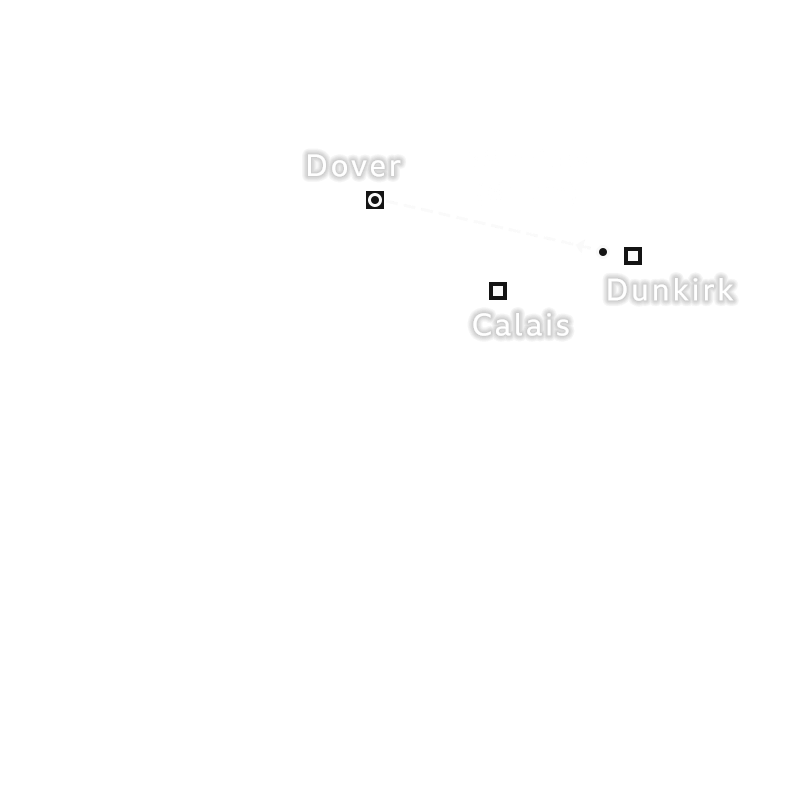

As evening draws in, the family are told by smugglers the time is right to leave and they join at least 28 others on board an arranged bus to Loon-Plage, a stretch of coastline between Dunkirk and Calais.

The BBC has established 20 of these passengers were from Iraqi Kurdistan.

The journey to the beach is short - just 10 minutes - and many on the bus begin to contact family back home to let them know they are about to leave France.

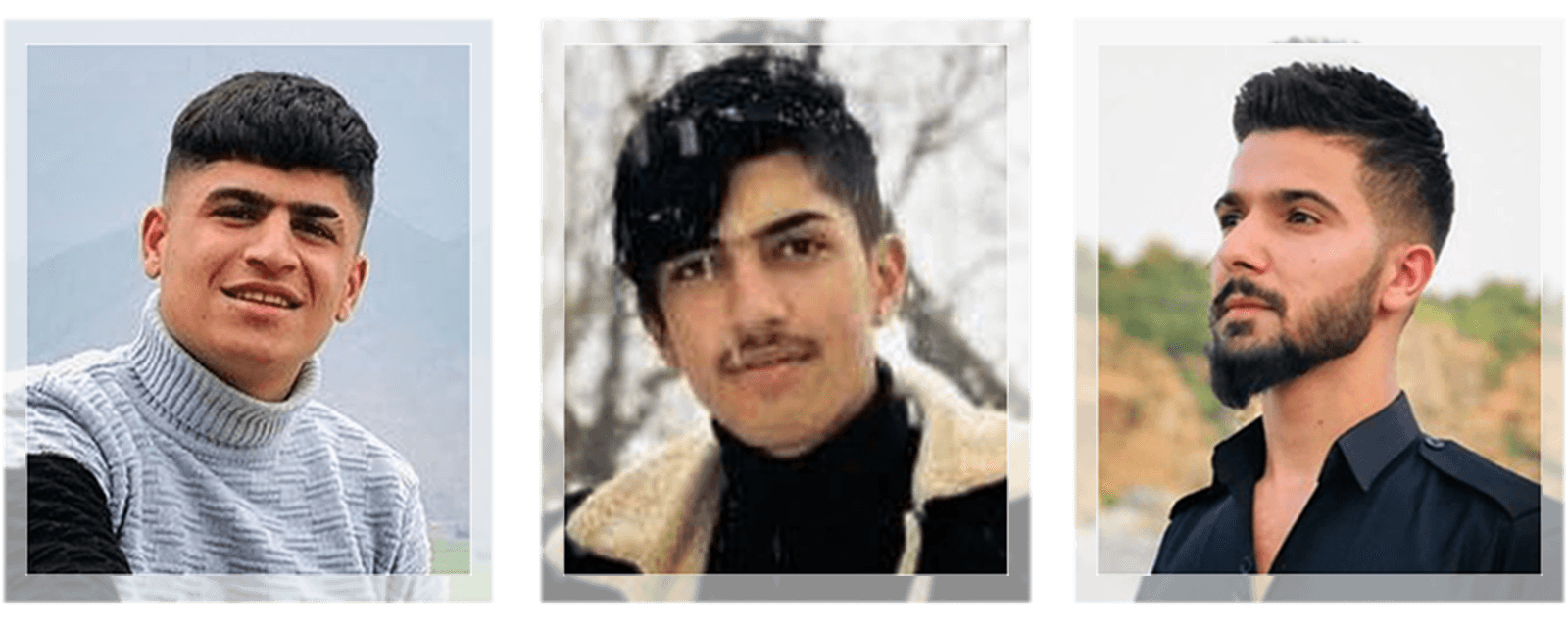

Best friends Rezhwan Yasin Hassan, 19, Zanyar Mustafa Mina, 20 and Mohammed Qadir Aulla, 21, all from Iraqi Kurdistan, are among those messaging home from a shared phone.

19:45

A little later, another group of friends and acquaintances, who were also on the bus, contact their families in Iraq from several shared phones.

The youngest are Pshtiwan Rasul Farka and Twana Mamand Mohammed, both 18, and 19-year-old Mohammed Hussein Mohammed. Also travelling with them are “Hybar” Bryar Hamad Abdulrahman, 23, Afrasia Ahmed Mohammed, 27, “Harem” Serkaut Perot Muhammad, 28, Shakar Ali Pirot, 30, and Hassan Mohammed Ali, 37.

Among them is one Iranian, Sirwan Alipour, 23.

Bryar (pictured above, top-right) calls his mum and says he will contact her “when on the other side of the Channel”.

20:00

Hadiya, the 22-year-old hoping to train as a doctor, texts her father - the man who made this trip possible. He sold the family home and borrowed money to raise the $42,000 (£32,000) needed.

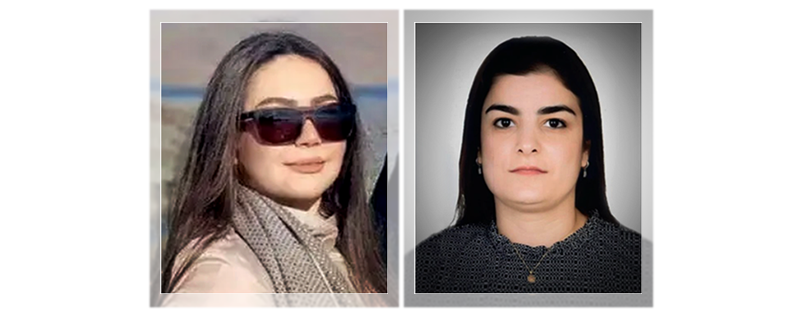

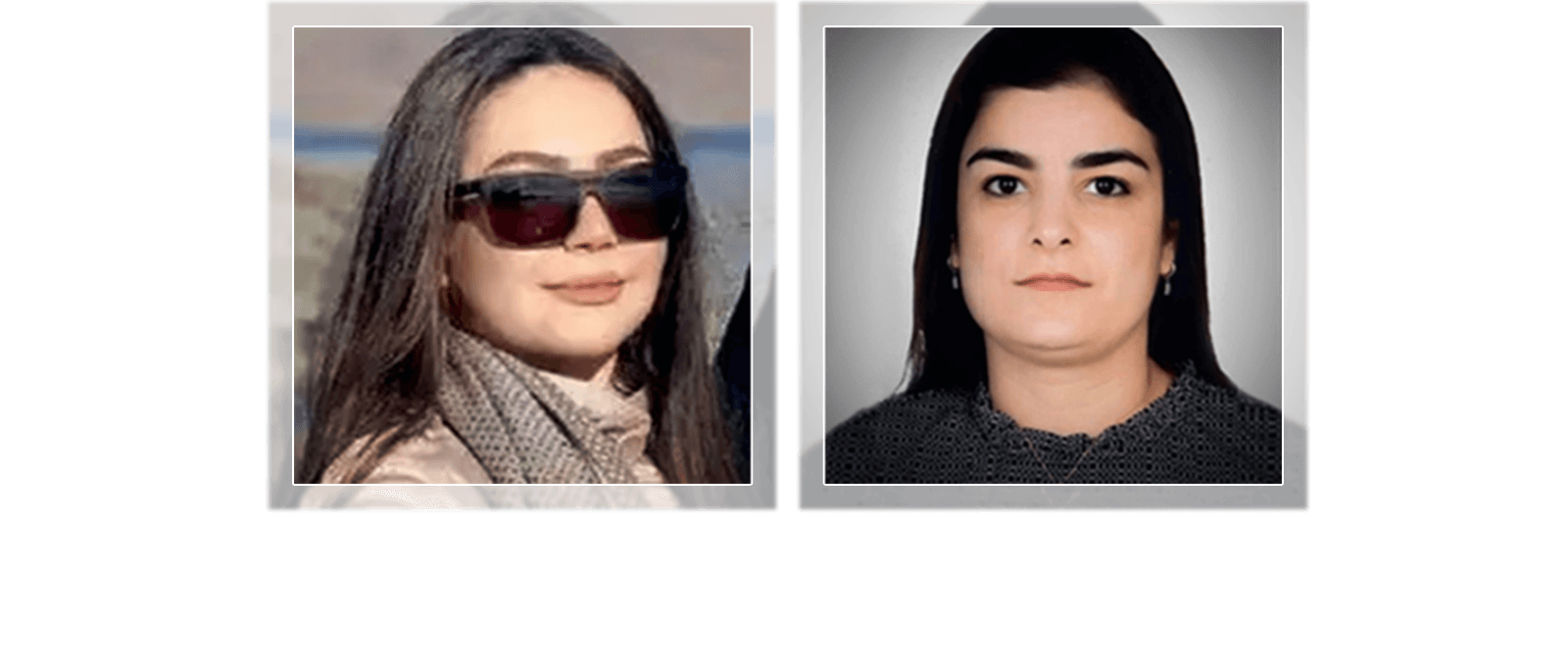

Iraqi Kurd “Baran” Maryam Nuri Mohamed Amin 24, trying to reach her fiance in the UK, and her friend, 32-year-old Mhabad Ahmad Ali, are also getting on the boat.

22:00

To go ahead with the launch, conditions need to be right – no police patrols, clear skies and a calm sea. At about 22:00 French time, traffickers give the migrants the final green light to cross.

Some rescuers call such times “migrant weather” because it is when many decide to make the journey. But they warn it is not the wind that is the biggest challenge. It is the freezing air and sea temperatures.

A number of dinghies are dug up from their hiding places along the dunes, where they have been kept out of view of the police.

At least six boats are launching that night.

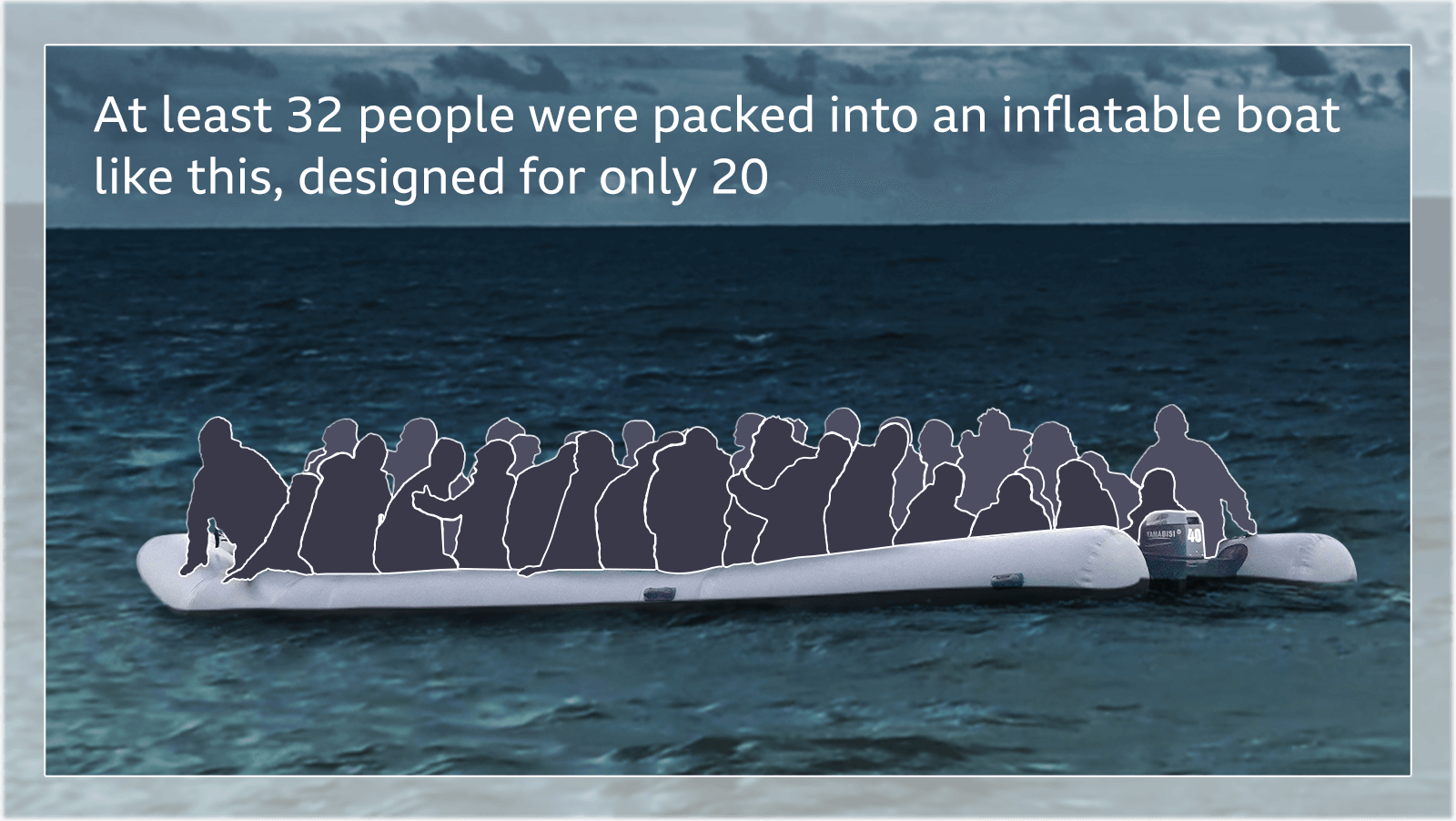

Hadiya and her family along with everyone else on the bus are allocated a 10m- (33-ft-) long, rubber inflatable dinghy with a motor attached at the rear. A boat like this can be bought second-hand for £400 ($531). It has no solid base and isn’t designed to safely carry more than 20 people.

But this small dinghy leaves France with a human cargo of at least 32 adults and children on board.

22:50

The boat pushes out into the open waters and Pshtiwan sends his last voice message home - the dinghy motor heard in the background.

Overloaded, the boat makes slow progress - partly because of its excess weight - as it heads north-west into the night. Its passengers cling on to each other, and to the sides of the vessel, as the waves increase in size.

Another group of migrants making the same journey just an hour later describe “big waves and stormy weather”. They are left soaking wet and freezing cold. Some are also seasick, and they end up aborting their journey and returning to France.

Wednesday 24 November, 01:30

Dinghy engulfed

Hadiya and her group begin to run into difficulties.

As the boat reaches the middle of the Channel, its right side begins to deflate and the vessel starts taking on water.

“Some people were pumping air into it and others were bailing the water from the boat,” 21-year-old Iraqi Kurd Mohammed Shekha Ahmad, one of only two survivors, tells Kurdish media network, Rudaw.

Baran messages her fiance in the UK, Karzan, on Snapchat. She describes how the boat is losing air and is taking on water, but jokes and tries to reassure him things will be fine. Those steering the boat are trying hard to keep it afloat, she says, and she is sure that the authorities will rescue them soon.

Passengers begin to debate flagging down a ship they have spotted in the distance, but the consensus is they should push on to Britain.

02:30

But worse is to come. A short time later, the boat’s engine cuts out, leaving the vessel and its passengers at the mercy of the Channel’s currents.

The boat begins to be swallowed by the waves.

“Within 30 minutes the whole boat had sunk,” the boat’s other survivor, Mohammed Isa Omar, 28, from Somalia, tells the BBC.

As they are plunged into the freezing water, the group cling together and to what’s left of the deflated dinghy, to stop themselves drifting away from each other.

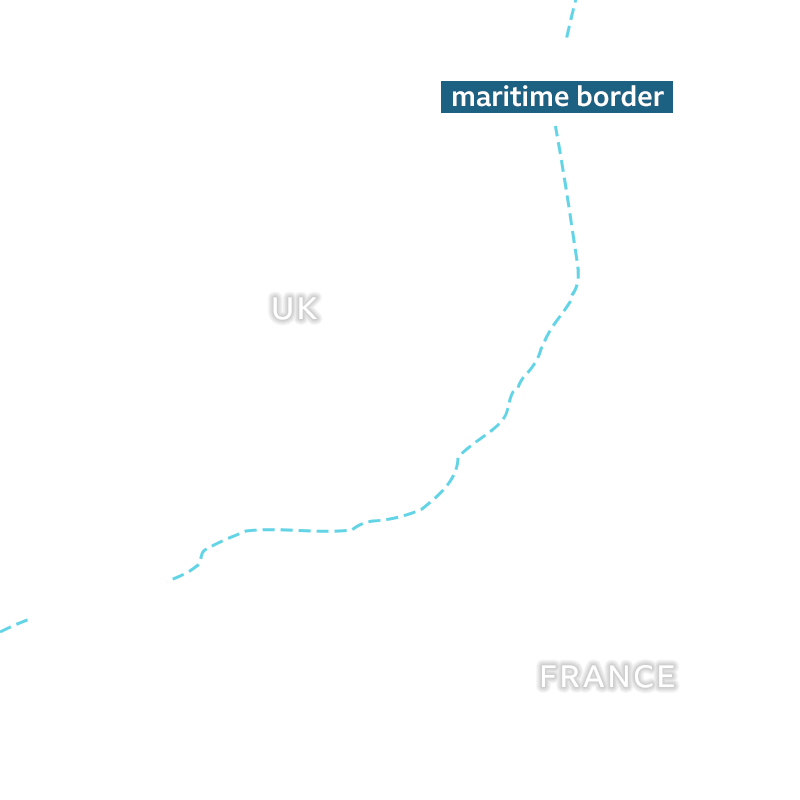

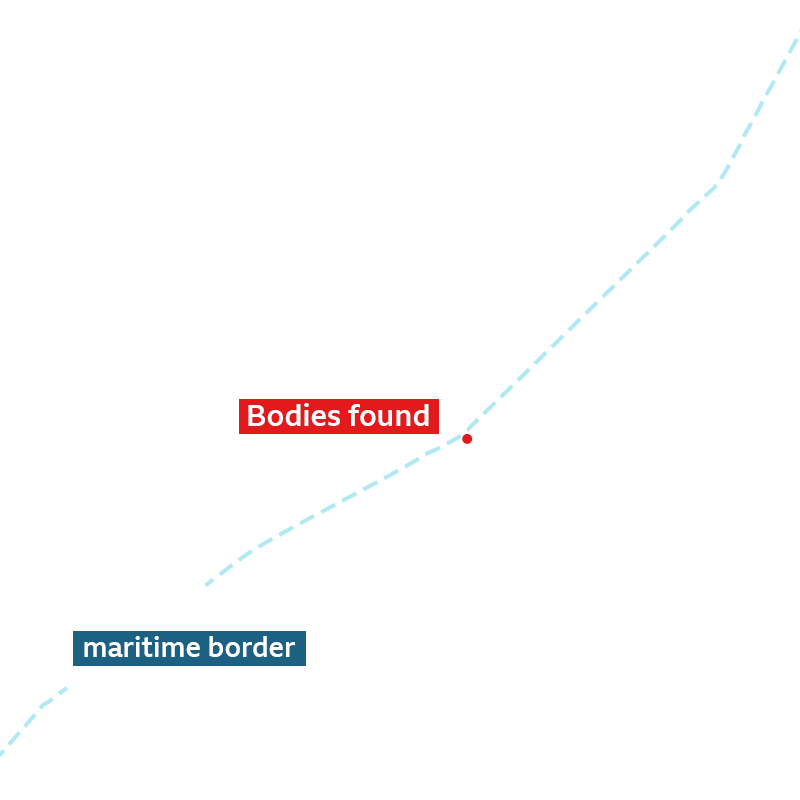

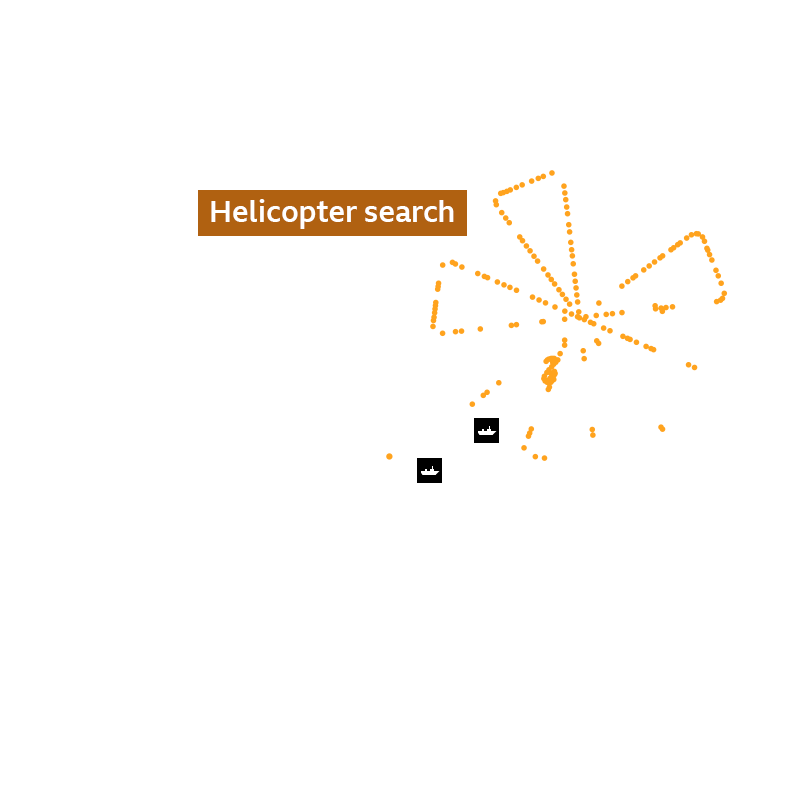

They have travelled at least 30km (19 miles) from the beach where they first departed. BBC analysis of the current and ship tracking data suggests they are now near the maritime line that marks the start of British territorial waters.

As they hold each other’s hands, those who can, including 16-year-old Mubin - Hadiya’s little brother - phone both the French and English authorities for help.

Mid-conversation with her fiance, Baran drops off Snapchat.

03:42

At least two of the group get through to the British authorities on the phone, who ask for the group’s location and tell them to keep their mobile torches on. But those passengers’ phones fall into the water before they can send the details, survivors say.

Around this time, Shakar Ali Pirot sends a voice message to his family.

He says if he is saved he will toss his phone into the waves - something many migrants have told the BBC they are ordered to do by smugglers to protect the people-traffickers’ identities. Some also say they do it to hide details that may prevent their asylum claims being accepted once on UK soil.

Shakar’s voice message is believed to be the last known communication from the boat.

According to the WhatsApp exchange between Shakar and his family, seen by the BBC, his phone stays online until 04:14 French time, but he sends no more messages.

The boat is now completely submerged and all the passengers are treading water. Hypothermia sets in.

“I saw people dying in front of me,” says survivor Mohammed Isa Omar.

He is a strong swimmer and he makes for a nearby vessel.

09:00

A second migrant boat - which set off after the one carrying Hadiya and her family - arrives in the middle of the Channel. In the early morning light they see bodies in the water. The passengers of that boat call the French authorities for help.

“I saw some bodies without lifejackets and others with [them], but the worst type, the very cheap ones,” one anonymous man says in an audio message heard by the BBC. “Because I was in shock, I did not see their faces, but they looked like they must have been dead a while. Maybe two hours after their boat capsized.”

This second dinghy later arrives safely in the UK.

13:58

Mayday

Nearly 12 hours have passed since Hadiya and her group fell into the water.

Then just before 14:00, 37-year-old French fisherman Karl Maquinghen and his crew, on board their trawler Saint Jacques II, spot 15 bodies in the water.

“We felt sick,” he tells the BBC. “Despite working as a fisherman for 20 years… this was the first time I’ve ever seen something like this. We’ve seen empty deflated boats, but never bodies.”

Karl says many of the victims wearing life jackets had not connected the crotch strap correctly, which would have made it harder for them to keep their heads above water.

Karl and his crew quickly raise the alarm and the nearby French navy vessel, FS Flamant - about 5km (3 miles) away - responds.

15:45

A total of 27 bodies are recovered, including those of seven women, two teenagers and one young girl.

The two survivors claim the dinghy had crossed over into British waters. They say they continued to make desperate calls to both the British and French authorities, but were told by both sides to call the other.

It is broadly accepted that a country has responsibility for maritime rescues in its territorial waters, although anyone finding a vessel in distress is expected to help with a rescue.

The French maritime authorities (the Maritime Prefecture of the Channel and the North Sea) say they were “not aware this boat was in difficulty prior to the alert raised by a fishing vessel”, referencing the Saint Jacques II. They add that on that same night, 106 people were saved during three different operations.

However, according to the French newspaper Le Monde, a source inside the official police investigation has revealed that the itemised phone bills of the survivors confirm claims they called the French authorities for help.

The UK Home Office maintains the boat was never in British territory and has rejected any claims they failed to respond to the sunken vessel.

Analysis exclusive to the BBC suggests the migrant boat came close to, but never entered UK waters.

Weather and water-current data from that location throughout the day suggests the boat would certainly have been pushed around, but we can deduce from the location the migrants were found in, and the direction of the currents, that waves would not have pushed them back from British waters.

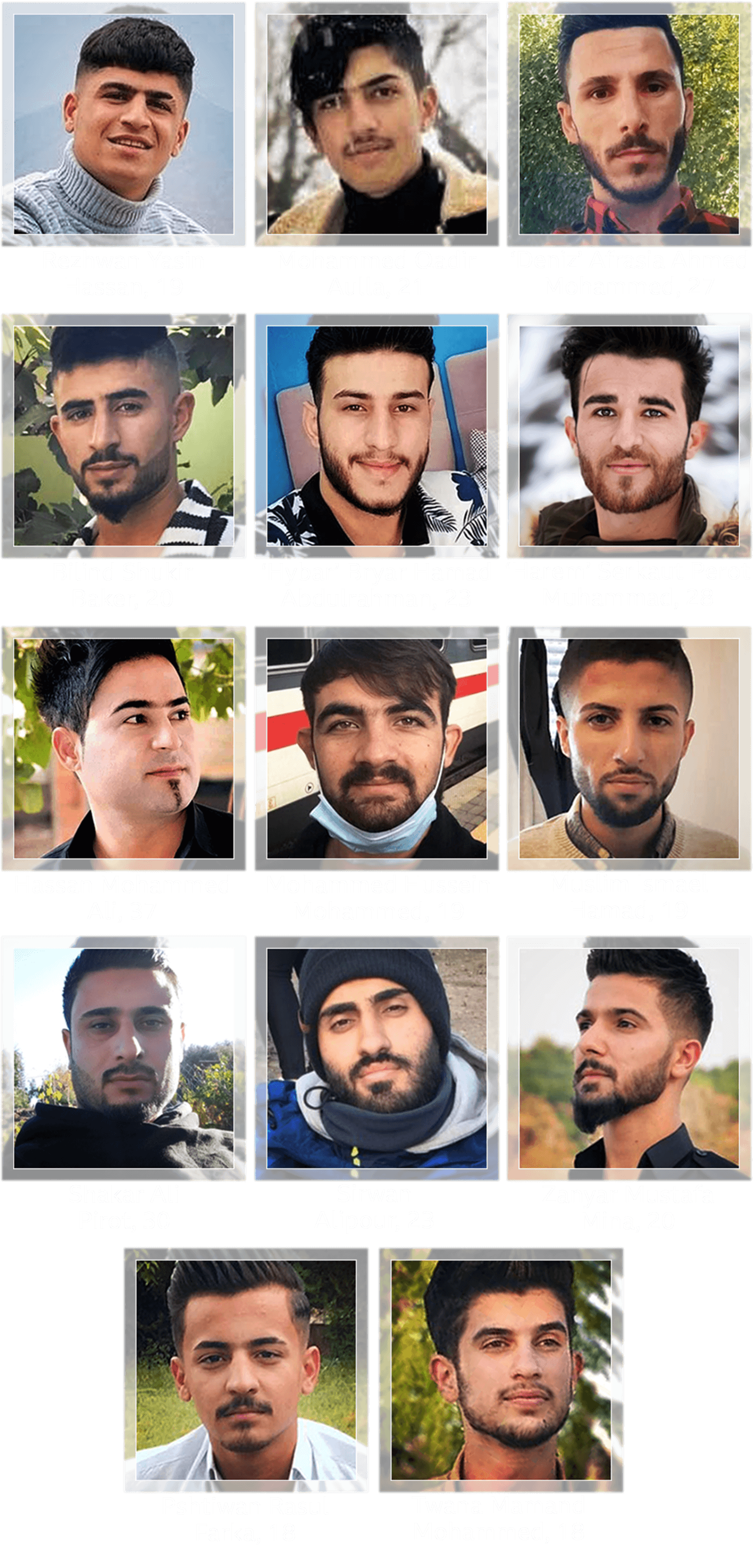

The victims

The BBC has confirmed at least 30 people died that night - by far the worst migrant tragedy ever recorded in the Channel. We have established, through help from many families in Iraqi Kurdistan, the identities of 20 of those on board.

This includes Hadiya and her family, including her seven-year-old little sister Hasti.

There is also Baran and her friend Mhabad; best friends, Rezhwan and Mohammed Qadir, and young men Afrasia, Bilind, Bryar, Harem, Hassan, Mohammed Hussein, Muslim, Shakar and Sirwan.

The body of Zanyar - Rezhwan and Mohammed’s best friend - has not yet been recovered. Pshtiwan and Twana are also still missing.

All of them were economic migrants and nearly all of them had previously tried - and failed - to get to Britain via legal routes multiple times. They had all also attempted to cross the Channel at least three, and in some cases six, times before in small boats.

The French authorities told the BBC 10 other passengers who died have been identified as three Ethiopians, a woman from Somalia, four men from Afghanistan, a man from Egypt and one person from Vietnam.

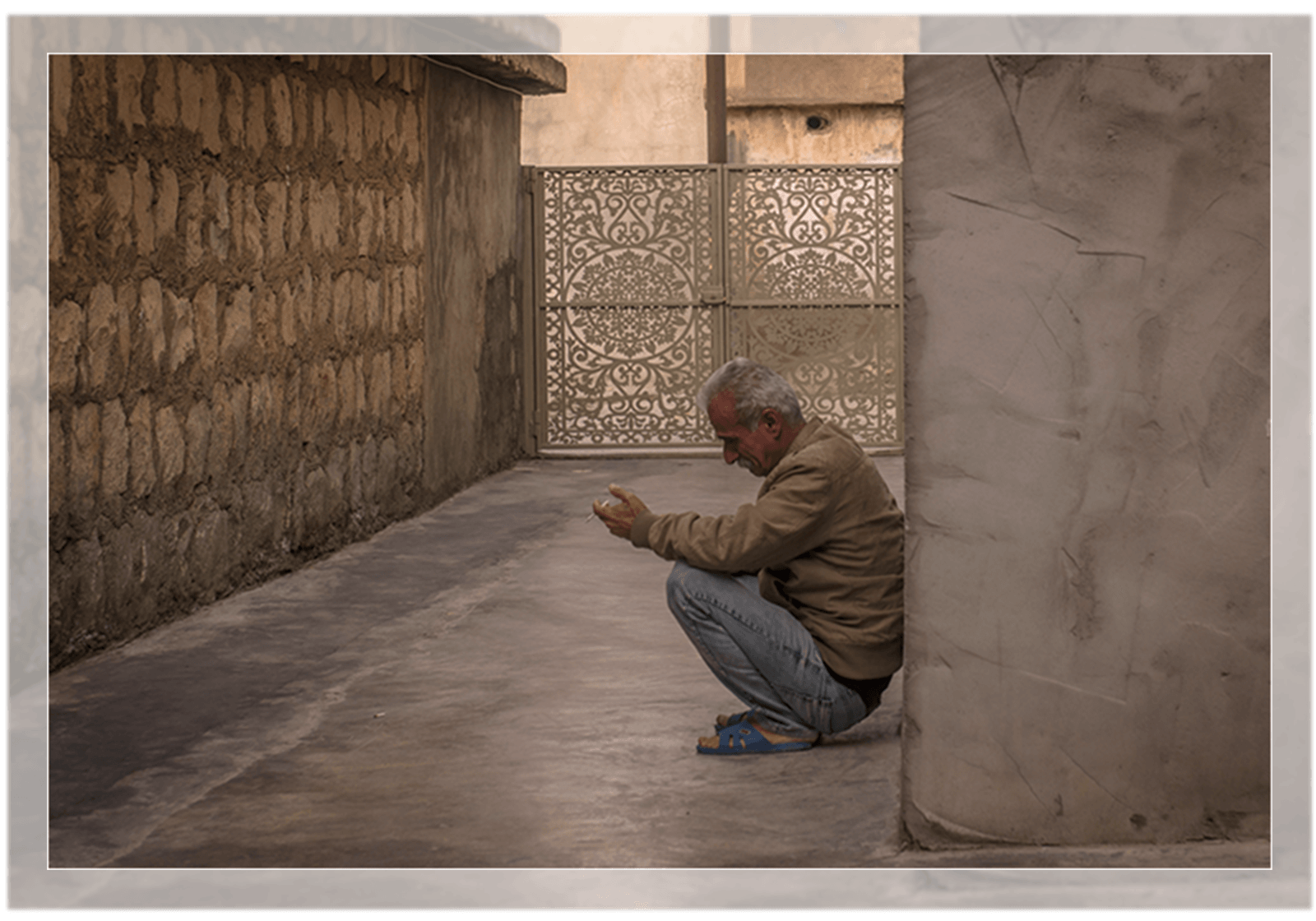

For Rzgar Hussein Mohammed, the pain of losing his wife and three children to the waters that night is too much to bear.

“I can’t do anything,” he tells the BBC. “I can’t eat or sleep. I am going crazy. Nobody can live without a family.”

A month on, despite freezing temperatures, hundreds of migrants have continued to cross the Channel each week.

Evicted from their makeshift camps by the French police in Calais, many say they have little choice but to take their chances with the Channel’s waves.

The Channel beaches that host a lethal trade in human hope

The Channel beaches that host a lethal trade in human hope

Why can't migrant Channel crossings be stopped?

Why can't migrant Channel crossings be stopped?

Migrant tragedy is biggest loss of life in Channel

Migrant tragedy is biggest loss of life in Channel