The talk-show hosts telling Russians what to believe on Ukraine

Meet the famous TV presenters now selling the Kremlin’s failing military campaign as a ‘holy war’ for survival

Click here to launch the story - APP TESTINGScroll down to start

Political talk shows play a powerful role in Russia

Day after day, millions tune in to see larger-than-life presenters discuss what is happening across the border in Ukraine. Their shows are selling a compelling story - one where Russia is the hero and Ukraine and the West the villains.

These utterly loyal hosts have demonised Ukraine since 2014, when it aligned itself more closely with Europe. When Russia invaded last year, they framed it as a swift operation to "liberate" Ukrainians but their rhetoric changed as progress on the battlefield stalled.

Meet four of the most famous faces on TV and listen to what they’ve told millions of Russians.

"Hello. This is Meeting Place, where everything becomes clear."

Andrey Norkin, NTV

Vladimir Solovyov

Vladimir Solovyov is well-known for his emotional and often vulgar outbursts.

He has a prime-time TV show, daily podcasts and his own streaming channel, making him a voice that is hard to avoid.

He often refers to the conflict in Ukraine in religious terms, portraying it as a “holy war” and a clash of civilisations that Russia can't afford to lose.

If you think we'll stop at Ukraine, think it through 300 times. I'll remind you that Ukraine is just an intermediate step in the establishment of the strategic security of the Russian Federation.

Vladimir Solovyov, Solovyov Live

Olga Skabeyeva

Olga Skabeyeva is a rising star in the world of Russian political talk shows.

A tough-talking and fiery co-host alongside her husband Yevgeny Popov, critics have referred to the ultranationalist as the “Iron Doll”.

She is one of the most influential TV hosts shaping the way Russian audiences view the war.

Now we will have to demilitarise the whole of Nato. I've said it many times, then people gasp in shock. This is what we call Worrld War 3.

Olga Skabeyeva, Rossiya 1

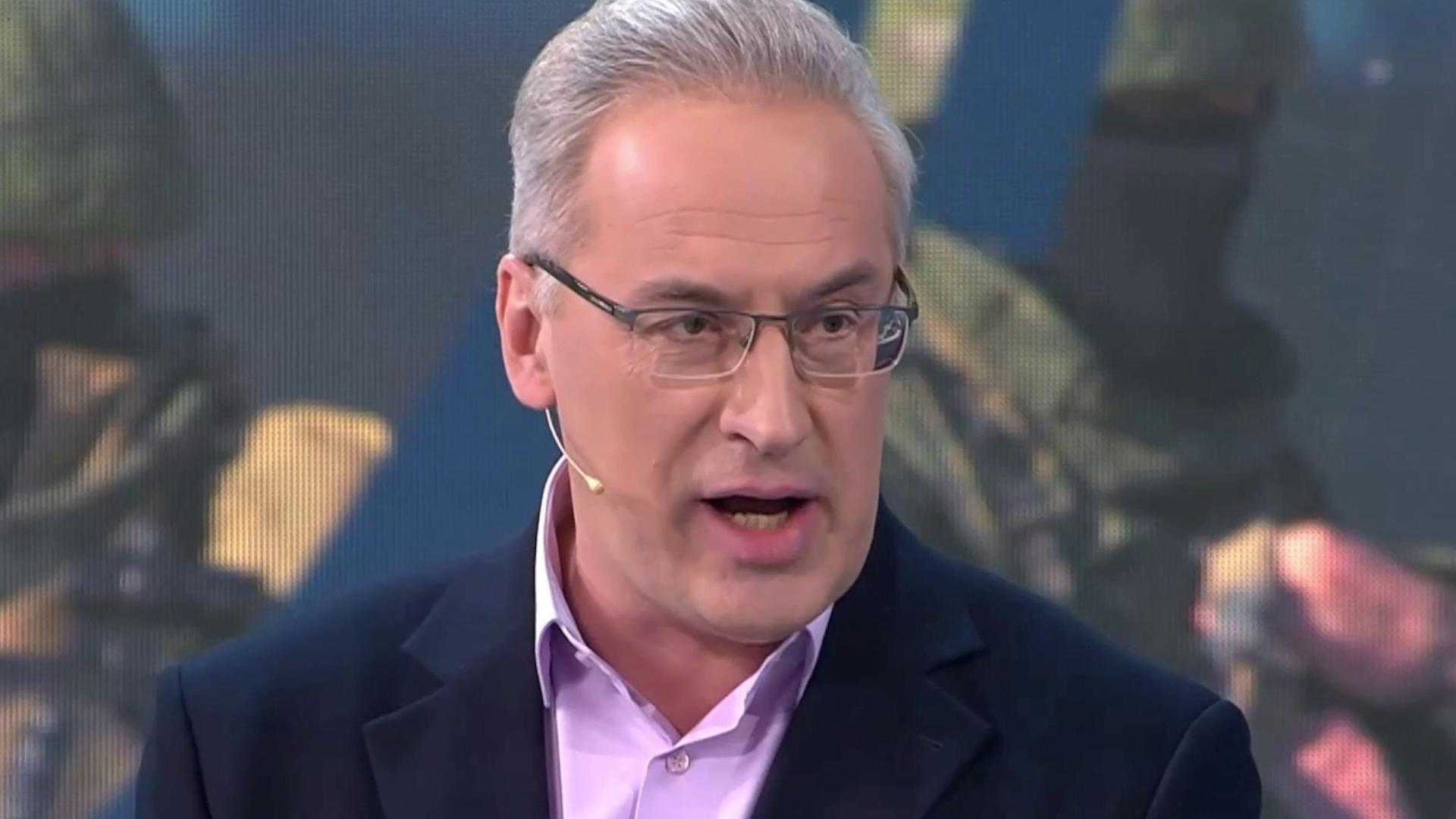

Andrey Norkin

Andrey Norkin is an experienced host and one of the old guard whose TV career began before President Putin tightened his grip on the media.

He has adapted to this new environment but is open about the Kremlin's tight control of state media and was reluctant to share his views on Russia’s withdrawal from Kherson last year, saying: “I don’t want to go to jail.”

He has a calmer presence than his more animated peers, although his show can still be chaotic, with guests shouting over each other.

Meeting Place on NTV is not only the friendliest talk show on television, but also a show that likes jokes. Even dark humour.

Andrey Norkin, NTV

Margarita Simonyan

Margarita Simonyan’s meteoric rise was reflected when she was appointed editor-in-chief of RT, Russia’s main international propaganda outlet, at just 25 years old.

She once described information as a “weapon like any other” and is fervently loyal to President Putin, receiving a state award for her work personally from him last year.

As a frequent guest on shows including Vladimir Solovyov’s, Simonyan is a very familiar face on Russian TV.

I recently re-read some of the letters I sent back home when I studied in the US. I wrote to my parents, 'I get the sense that this isn’t a country, but a kindergarten for mentally disabled children'.

Margarita Simonyan, Rossiya 1

How the narrative has changed

These four personalities have driven the pro-Kremlin narrative of the war in Ukraine since Russia’s invasion a year ago.

They’ve celebrated victories on the battlefield and shrugged off defeats as small setbacks in a war they believe Russia can only win.

Here’s an insight into some of the recurring themes in their coverage and how their tone has changed over the course of the war.

A ‘special military operation’

When Russia invaded Ukraine in February last year, the talking heads on TV were confident of a quick victory against what they viewed as an inferior enemy.

President Putin referred to the invasion as a “special military operation” rather than a war and a former general on Olga Skabeyeva’s show predicted it would take “a week maximum”.

As Russian helicopters landed on the outskirts of Kyiv, Skabeyeva herself joked about President Volodymyr Zelensky fleeing to London or Paris.

All of Ukraine's air defences and air bases have been completely disabled. Ukraine's border guards are not resisting.

Olga Skabeyeva, Rossiya 1

The ‘denazification’ of Ukraine

The justification for Russia’s invasion has often centred on the so-called “denazification” of Ukraine, with presenters alleging that the country had been taken over by far-right groups and neo-Nazis.

While there were far-right groups in Ukraine before the invasion, they made up a small minority and played no part in the country’s government.

That hasn’t stopped them talking up the idea of saving “ordinary people” in Ukraine from the “madness of Nazism”.

Our most important task is to free normal people. Free them from the guns held against their backs by these Nazis.

Margarita Simonyan, TVC

The threat of nuclear weapons

As the months went by, and Russia withdrew from around Kyiv and saw its forces pushed back in the south and east of the country, talk of a quick victory disappeared.

In a bid to reassure viewers that Russia remained strong, the talk show hosts increasingly discussed the country’s nuclear weapons arsenal and the potential use of them to change the course of the war.

And on the day of the Queen’s funeral at Westminster Abbey last September, attended by several Western leaders, Olga Skabeyeva joked about it being a good time to “nuke London”.

If Russia suffers so greatly, that we'll have no choice but to erespond. And we will respond with all means available.

Andrey Norkin, NTV

A clash of civilisations

As the setbacks have continued and Russia’s forces have been left increasingly humbled, the Kremlin media machine has looked for new ways to sell the war to the Russian people.

More and more it has been framed as a struggle against a depraved West which has rejected its Christian morals in favour of “non-traditional values”.

Offensive homophobic rhetoric escalated, with the West often labelled as “satanic”.

We're fighting against satanists. RThis is a holy war and we have to win!

Vladimir Solovyov, Solovyov Live

Backing Putin in long war

On state TV, rare discussion of Russia’s failure to meet its military objectives concludes not with criticism of President Putin, but attacks on lacklustre generals on the front line.

In recent months, the hosts have been preparing their audience for a longer conflict against the West as Ukraine’s allies have increased their military support for President Zelensky.

Speaking on his show in December, Vladimir Solovyov said: “There’s no doubt there is a difficult war ahead of us.”

Firstly, it's a war for Russia's survival. Nobod'y planning to give up. This will be a long war and not just with Ukraine. Ukraine is just a fragment. If they manage to push us back further, they won't stop. We need to prepare for a long, serious and great war.

Vladimir Solovyov, Rossiya 1

TV is key to Putin's power

Together, these four characters front a powerful media machine which only tells Russians what the Kremlin wants them to hear.

Polling suggests that TV remains far and away the most popular information source for Russians, with around two-thirds of the population receiving their news from Kremlin-controlled channels.

And with no end to the conflict in sight, the inevitable prospect of eventual war fatigue means their importance for the Kremlin’s grip on Russian public opinion will surely only grow.

Ukraine: Watching the war on Russian TV - a whole different story

Ukraine: Watching the war on Russian TV - a whole different story

Ukraine war: Russians fed twisted picture and one voice - that of Putin

Ukraine war: Russians fed twisted picture and one voice - that of Putin

Ukraine war: Russians kept in the dark by internet search

Ukraine war: Russians kept in the dark by internet search