It’s Eurovision time!

This year Eurovision goes global, as fans around the world are invited to join the voting.

Here’s our guide to the glitz, the kitsch and the glory of the world’s biggest singing competition.

It’s a competition, so it has to have some rules.

Rule one: It must be a new song - new tune and new lyrics.

Rule two: The performance must be no longer than three minutes.

Rule three: It must be sung live. No lip-syncing!

Rule four: No more than six people on stage.

Rule five: No politics. (Though this one can be a little slippery.)

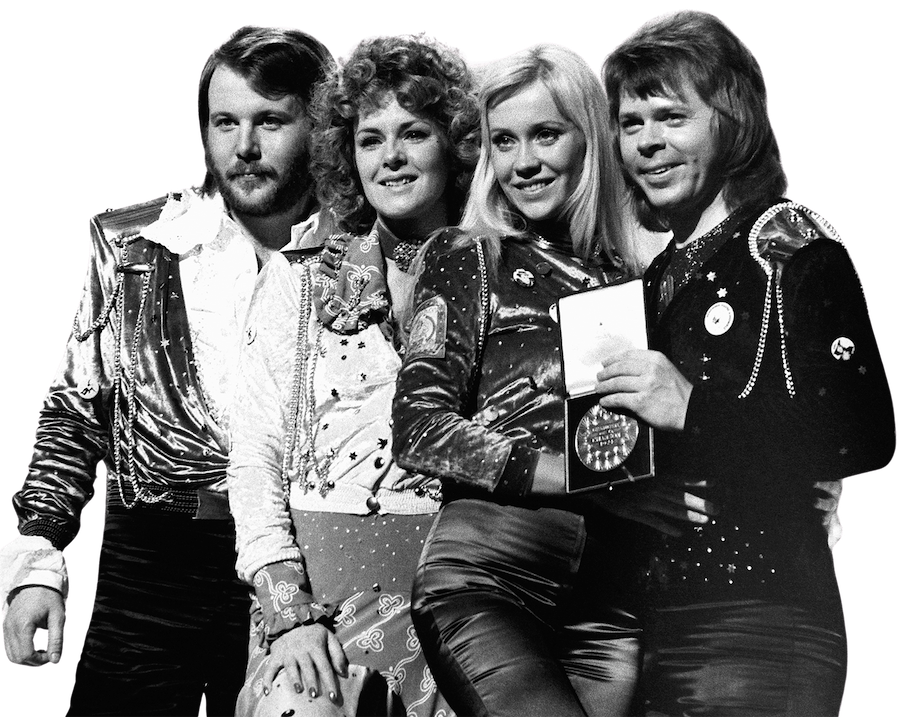

ABBA

Eurovision’s most famous winners appeared during a four-year window in the 1970s when performers were allowed to sing in any language. They seized the chance to sing in English and went on to pop superstardom - despite the UK giving them no points.

What about languages? Does everyone have to sing in their native language?

No. Since 1999, performers have been allowed to sing in any language.

Belgium even entered songs in a made-up language - twice!

Curse of song two

The second song to be performed at the final has never won the competition, and the second performer has rarely qualified from the semi-finals since they were introduced in 2004.

Thirty-seven countries have entered this year.

Twenty will qualify from the two semi-finals - both broadcast live with the winners decided by the television audience.

Six countries automatically qualify for the grand final: last year’s winners (Ukraine) plus the "big five" of France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UK.

These five effectively pay to play as they are the major funders of the EBU, which runs the contest.

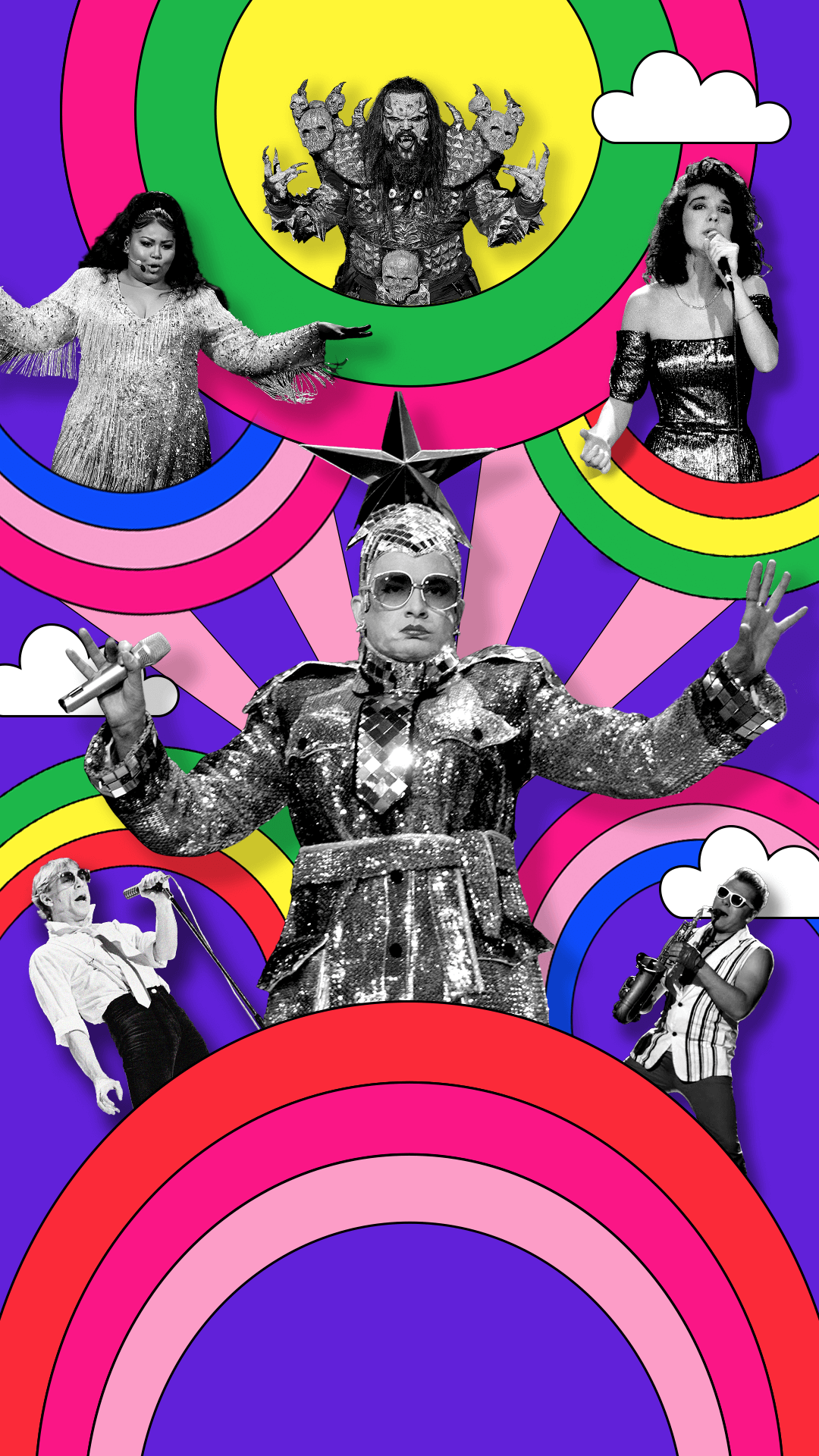

It's a song contest but the most memorable moments are often about what happens around the song.

Until 1971, only solo singers or duos were allowed to perform - and they had to use the house orchestra.

Most acts stood on the stage, sang their song, bowed and walked off.

It’s a little different now.

Since the introduction of audience voting, the staging has become almost as important as the song.

Creative teams use the latest technology to turn their three minutes into an event.

It’s led to some gloriously bizarre and memorable moments including…

2006: The lead singer of Lithuania’s LT United chants their inaccurately-named song We Are The Winners through a megaphone while a bald-headed man thrashes around as if fighting an invisible pack of dogs.

2007: Scooch sing Flying the Flag for the UK while dressed as airline cabin crew and making announcements about emergency exits and complimentary snacks.

Epic Sax Guy

The singers usually grab all the limelight but no-one remembers who was singing Moldova’s entry in 2010. All they remember is Epic Sax Guy and his bare-armed, hip-thrusting solo.

2010: Another memorable performance from Lithuania, as the five young men from InCulto finish Eastern European Funk by stripping down for a final strut in silver-sequinned hotpants.

2012: Ireland’s song Waterline is sung by Jedward, appearing for their second consecutive year, this time dressed as extras from a cheap 1970s Star Wars cash-in, leaping around a giant fountain of water jets before finally jumping into them and getting soaked.

2013: Romania’s Cezar, wearing a Dracula-inspired robe, sings It’s My Life in a high falsetto as three almost-naked dancers appear from beneath a blood-red plastic sheet.

Props

As staging has become more sophisticated they are seen less often, but some acts still add them for a little variety. From singers with foam-rubber guitars or battle-axe microphones, to dancers appearing on unicycles or trapped in giant, transparent bubbles.

2019: Iceland’s Hatari bring “industrial bondage” with their gentle ditty Hate Will Prevail, featuring a chained man hitting a giant metal globe with a sledgehammer while the lead singer screams in Icelandic.

2019: Australia’s Kate Miller-Heidke, in a long white dress, chirps her song Zero Gravity while suspended on a giant, waggling pole, like some sort of intergalactic Christmas tree fairy.

It’s a song contest, so every entry has to have lyrics.

How many words do you need for a song?

At Eurovision there's no rule on how many or how few words you can use.

Norway pushed the boundaries in 1995 with the song Nocturne, which had just 24 words and a two-minute instrumental section - but went on to win.

Johnny Logan

Arguably the king of Eurovision, he is the only performer to have won Eurovision twice - with What's Another Year in 1980 and Hold Me Now in 1987 - plus he also wrote Linda Martin's winning song in 1992 and her earlier, second-place song in 1984.

Eurovision was once known for novelty songs with nonsense lyrics, intended to cross the language divide.

And it worked! Here are the hooks from three winners:

"My heart goes boom bang-a-bang, boom bang-a-bang when you are near." Lulu, United Kingdom, 1969

"Listen to a song that goes ding ding-a-dong and the world looks sunny. Everyone is funny, when they sing a song that goes ding-dang-dong." Teach-In, Netherlands, 1975

"Diggi-loo diggi-ley, life is goin' my way." Herreys, Sweden, 1984

Yodeling

Or other types of indigenous singing, such as Yoik from the Sami, native to Finland, Norway and Sweden, or the Eastern European ‘white voice’ folk style.

Host countries often use the interval to show off an aspect of their national culture, most famously Ireland, in 1994, when Riverdance accidentally launched an international dance sensation.

Let’s celebrate Ukraine at Eurovision.

Eurovision is in Liverpool this year. It should be in Ukraine, following Kalush Orchestra’s win with Stefania in 2022, but the war made staging it there impossible, so the BBC is hosting on Ukraine's behalf.

Ukraine made its debut in 2003 and has become a major Eurovision player, having won three times and twice been runner-up.

It won in its second year with Ruslana’s leather miniskirt and thigh-high boot triumph Wild Dances.

Verka Serduchka

In 2007, drag artist Verka almost became Ukraine’s second winner with a display of enthusiastic, high-energy arm-waving in a tin foil, star-topped outfit - a Eurovision classic.

Ukraine has successfully blended traditional and contemporary musical styles in many of its songs.

Last year’s winners Kalush Orchestra mixed traditional instruments - two regional flutes, the sopilka and telenka - with folk song and rap.

Traditional instruments

Countries often give a flavour of their distinctive musical heritage through the use of folk instruments. Keep an eye - and ear - open for native drums, flutes, whistles, balkan bagpipes, Scandinavian fiddles, and many variations on the lute or harp.

Ukraine has also courted controversy in a competition which seeks to avoid politics.

In 2016, Jamala's winning song 1944, about the Soviet deportation of ethnic Crimeans, was seen by many as a reference to Russia's 2014 annexation of Crimea.

And before that, when Verka Serduchka had repeatedly sung "Lasha Tumbai" in her heavy Ukrainian accent, it sounded a lot like “Russia, goodbye”.

It’s a contest not a concert, so there has to be a winner.

After all the performances, the real drama: the voting!

Jahn Teigen

In 1978, he became famous as the first singer under the modern scoring system to finish with "nul points" with the song Mil Etter Mil (Mile After Mile). He became a celebrity in Norway, the song was a huge hit and he went on to compete twice more.

Every country in the final awards two sets of scores: one from a jury of experts and one by the fans.

Each of their ten favourite songs is given points - but they can't vote for their own country's song.

Their favourite act receives 12 points, their second-favourite ten points, their third place gets eight points, and then seven points, and so on, down to one point for their tenth favourite.

Voting blocs

Here’s where politics strays into the contest. Which countries will vote for their neighbours? Look out for the Slavic vote, the Nordic vote, the francophone vote and Greece and Cyprus giving each other 12 points.

Eurovision was one of the first televised competitions to let the audience vote.

Fans in Austria, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK began voting by phone in 1997.

This year the rest of the world will be allowed to vote for the first time, with points given to the ten most popular songs worldwide.

A rule requires all the songs to be non-political and yet…

The international attention that comes with an event the size of Eurovision can lead to controversy.

Ukraine has not been alone in recent years in selecting songs which could be seen as aimed at Russia.

When the contest was held in Moscow in 2009, Georgia withdrew from the competition after Eurovision organisers asked for changes to some of their lyrics.

Their song was called We Don’t Wanna Put In, but the chorus sounded an awful lot like "We don’t want no Putin". (Russian forces had invaded Georgia the previous year.)

In 2013, at the end of her performance, Finland’s Krista Siegfrids revealed her song Marry Me was a proposal to another woman by kissing her female backing singer.

Not particularly controversial for much of Europe, but perhaps too much for Turkey, which quit Eurovision complaining about some of the competition rules, and for China which edited Siegfrids out of its broadcast.

Dana International

Eurovision’s first openly transgender singer became a Eurovision icon in 1998, winning with the dance-pop anthem Diva. Ultra-Orthodox Jewish groups in Israel were less than happy about the choice and she received death threats ahead of her performance.

Italy may be the only country to have banned one of its own songs when Gigliola Cinquetti performed Si (meaning "Yes") in 1974.

After selecting the song, the national broadcaster RAI became worried it might be seen as a message to vote "Yes" in upcoming referendum on banning divorce and decided not to show the performace.

The song finished second, the Italian public voted "No" and divorce remained legal.

Finally, there is the rumour that, after winning two years in a row, Ireland deliberately picked acts it hoped would lose in the mid-90s.

Some fans believe that Paul Harrington and Charlie McGettigan were chosen in 1994 because their gentle, acoustic song-writing was unfashionable and Ireland would avoid the cost of hosting for a third time.

If that was the reason, it backfired spectacularly because they won - and Ireland remains the only country to win Eurovision three times in a row.

Flag Parade

At the start of the grand final, all the finalists walk on to stage accompanied by their national flag.

During this year’s parade, listen out for a unique UK-Ukraine flavour as some much-loved former Ukrainian contestants sing their Eurovision entries woven in with British classics.

Watch all of Eurovision on BBC and BBC iPlayer.

Semi-final one: Tuesday 9 May

Semi-final two: Thursday 11 May

Grand final: Saturday 13 May

Eurovision 2023: A guide to every song

Eurovision 2023: A guide to every song

When and how to watch

When and how to watch

Eurovisioncast: The BBC's official Eurovision podcast

Eurovisioncast: The BBC's official Eurovision podcast