Counting Russia's dead in Ukraine - and what it says about the changing face of the war

Scroll to read moreRussia has a history of extraordinary secrecy over its wartime losses.

So when it invaded Ukraine, the BBC and its partners began painstakingly verifying and counting as many deaths as possible.

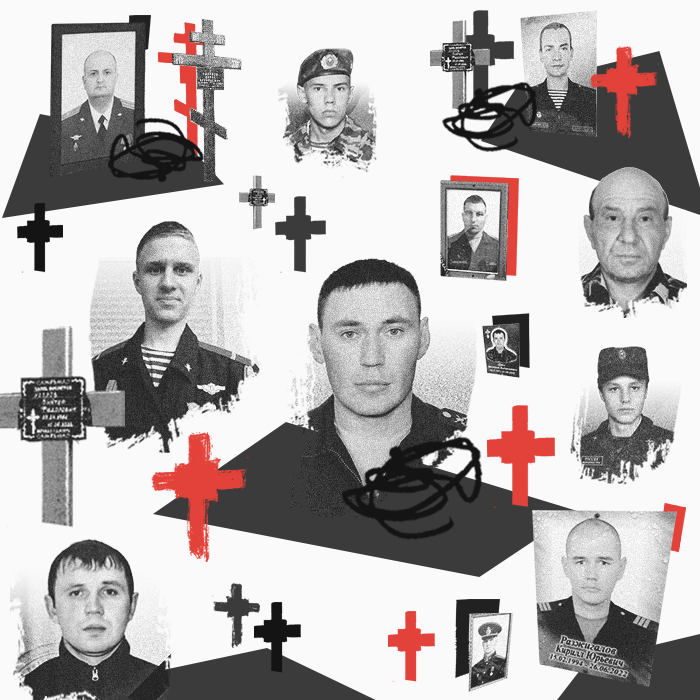

We identified more than 25,000 named individuals - people we know to have died - setting a bare minimum for Russia's total losses. Some of them are pictured here.

The count provides hard evidence of the war's impact on Russian forces. But it has also given answers to grieving families.

Some relatives did not even know what had happened to their loved ones until the BBC traced them.

Counting Russia's dead in Ukraine - and what it says about the changing face of the war

Russia has a history of extraordinary secrecy over its wartime losses.

So when it invaded Ukraine, the BBC and its partners began painstakingly verifying and counting as many deaths as possible.

We identified more than 25,000 named individuals - people we know to have died - setting a bare minimum for Russia's total losses. Some of them are pictured here.

The count provides hard evidence of the war's impact on Russian forces. But it has also given answers to grieving families.

Some relatives did not even know what had happened to their loved ones until the BBC traced them.

A tale of two recruits

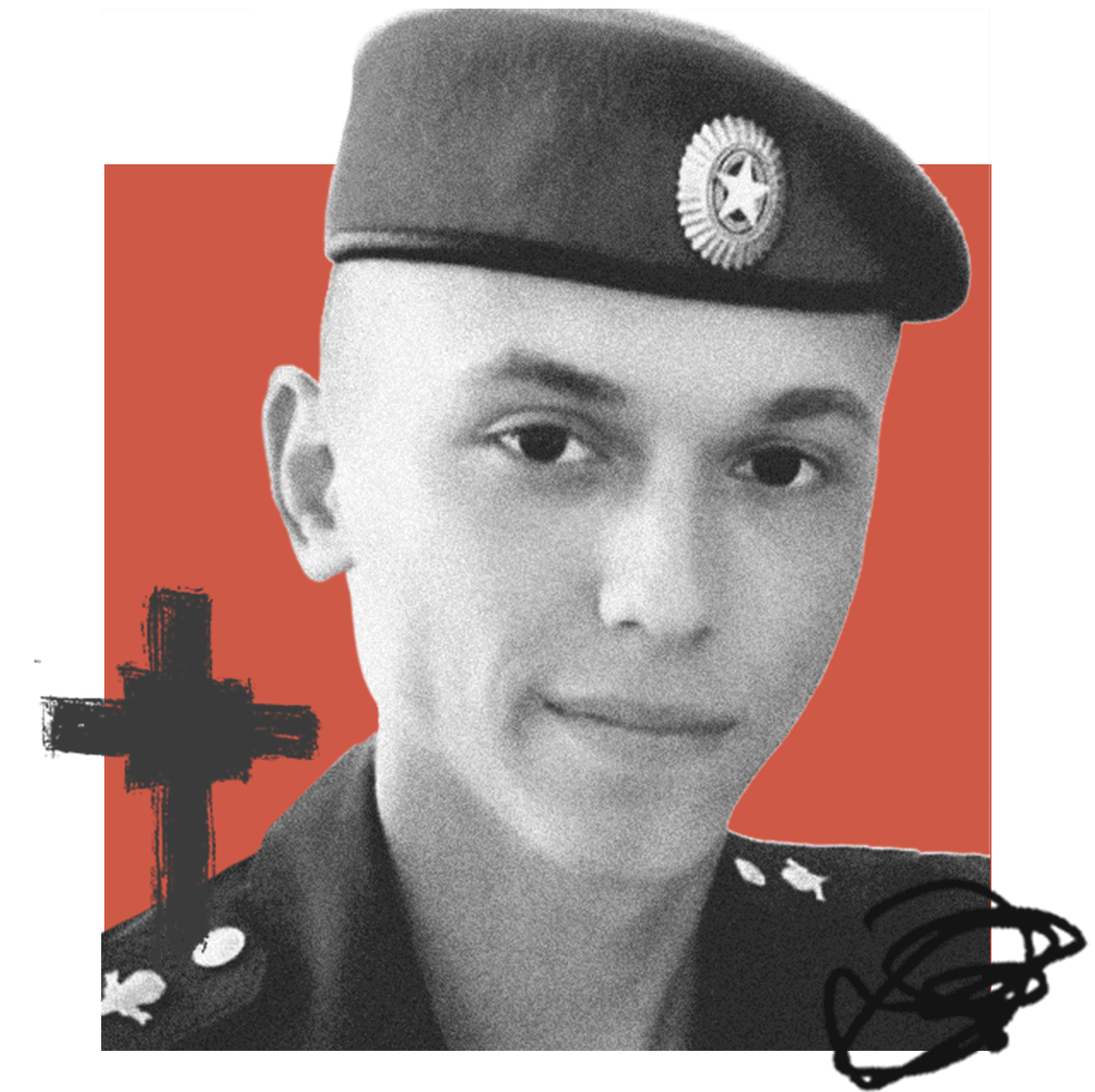

Sgt Nikita Loburets, a squad leader in Russian special forces, died on 20 May last year in a village in eastern Ukraine. He was 21.

Nearly a year later, relatives of Alexander Zubkov learned of his death during the fighting in Bakhmut. Aged 34 and serving a nine-year sentence for drug offences, he had joined the Wagner mercenary group in the hope of gaining his freedom.

These are just two of the 25,000 dead fighters who have been identified by the BBC, independent Russian media organisation Mediazona, and a team of volunteers, using information from official reports, newspapers, social media, and new memorials and graves.

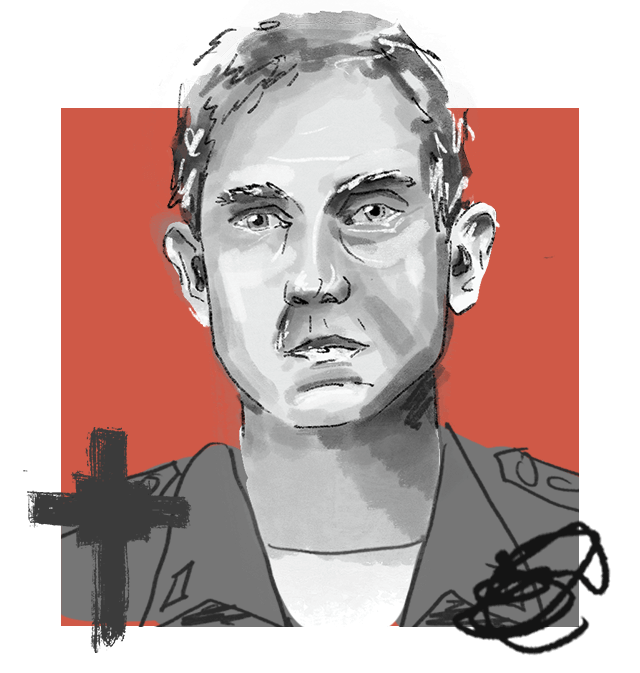

We can't tell the stories of all these thousands of deaths, but the data collected in the count uncovered a tale of the Russian army's changing face - represented by Sgt Loburets and Zubkov. It is a fighting force that is increasingly older and less well-trained as the deaths mount up.

When the war began, the typical Russian fighter whose death was recorded in the BBC's count was about 21 years old and a low-ranking professional soldier - just like Sgt Nikita Loburets.

Nikita Loburets

According to an account by his father, Konstantin, Loburets had wanted to be a paratrooper even before he left school in Bryansk, a city about 60 miles (100km) from the border with Ukraine. He began studying martial arts and learned how to parachute-jump before graduation.

Eventually, he won a place at the elite Ryazan Higher Airborne School, a training academy for Russian paratroopers, before joining the special forces brigade of the GRU, Russia’s military intelligence.

Nearly three months into the war, Sgt Loburets and a small unit of Russians were ambushed in a village north of Kharkiv and he was killed, his father said.

He was buried in the “Alley of Heroes” in his home city’s cemetery and was posthumously awarded the Order of Courage.

There were thousands of stories like his in the early months of the war.

Typical casualty in the first three months

Age: 21 | Professional soldier | Rank: Private

Typical casualty in the latest three months

Age: 34 | Prisoner | Rank: Unknown

But, a year later, they are less common.

In recent months, the typical Russian soldier killed in Ukraine is a 34-year-old convict recruited from prison.

But, a year later, they are less common.

In recent months, the typical Russian soldier killed in Ukraine is a 34-year-old convict recruited from prison.

Just like Alexander Zubkov.

Zubkov - prisoners fighting in Wagner units have no military rank - was born in Severodvinsk, a city on the White Sea on Russia’s north-west coast and a major shipyard for the Russian navy.

Alexander Zubkov

In 2014, court records show he was unemployed with a child when he was convicted of murder and sentenced to eight years and six months in prison.

Released on parole in 2020, he was back in court on drugs charges the following year - after he and an accomplice were caught with 600g of the illegal stimulant a-PVP.

The court sentenced him to a further nine years in prison, noting that he was divorced with a young child and a disabled sister whom he helped to care for.

When the Wagner group began recruiting from prisons, Zubkov joined up in November last year for the promise of 100,000 roubles ($1,250; £1,000) a month. If he completed six months’ service, he could expect to be freed.

But Zubkov died after five months, during Wagner’s fight to seize the eastern Ukrainian city of Bakhmut - the war’s bloodiest battle so far. He was buried in his home town on 28 April.

‘Burning through troops’

Zubkov and people like him are being used almost as “disposable troops”, says Jack Watling, an expert in land warfare at the Royal United Services Institute (Rusi), a defence think tank.

The prisoners appearing in the count of the dead range from petty thieves to gang leaders. In one case, one man died at the front after having been jailed for murdering a 92-year-old World War Two veteran.

Along with mobilised civilians, some of whom are picked up off the street or in shopping malls, they are ordered to skirmish constantly with Ukrainian forces, to wear them down and expose their positions to artillery.

“They send them forward in the expectation that they will be killed,” says Dr Watling. “And so the Russian military is burning through these troops at a significant rate.”

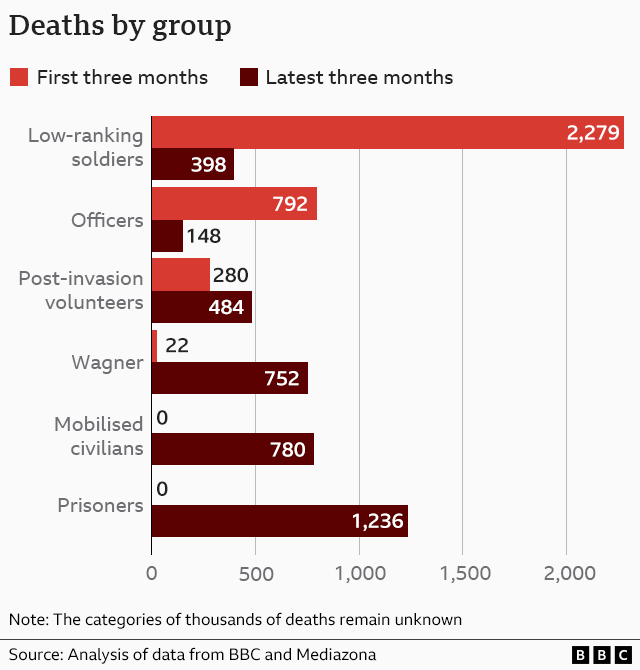

This change in tactics can be seen in the count.

Deaths by group

Russia lost large numbers of professional solders in the first three months of the war.

But in the latest three months, non-professional soldiers are dying in far greater numbers.

Russia lost large numbers of professional solders in the first three months of the war.

Deaths by group

| Rank | Dead |

|---|---|

| Officers | 792 |

| Privates and non-commissioned ranks | 2279 |

| Post-invasion volunteers | 280 |

| Wagner | 22 |

| Mobilised civilians | 0 |

| Prisoners | 0 |

But in the latest three months, non-professional soldiers are dying in far greater numbers.

Deaths by group

| Rank | Dead |

|---|---|

| Officers | 148 |

| Privates and non-commissioned ranks | 398 |

| Post-invasion volunteers | 484 |

| Wagner | 752 |

| Mobilised civilians | 780 |

| Prisoners | 1236 |

The categories of thousands of deaths remain unknown. Analysis of data from BBC and Mediazona.

Dr Watling says Russia is deliberately protecting its remaining professionals, using them to hold ground and carry out sniper attacks, and only to undertake rare assaults when conditions are right.

Expertise is harder to come by now. The BBC has confirmed the deaths of more than 2,100 Russian military officers - perhaps because Russia relies more on junior officers for combat leadership than Western countries, putting them in harm’s way. At least 242 held the rank of lieutenant-colonel or higher.

At least 159 fighter pilots have also been killed, according to the count. These cannot be replaced on a practical timescale: it takes a minimum of seven years and millions of dollars to train them.

Reuters

These losses have forced veterans out of retirement, such as Maj Gen Kanamat Botashev.

His military career was halted in 2012 when he borrowed an Su-27 fighter jet without permission and crashed it. In May last year, at the age of 63, he was piloting an Su-25 ground attack aircraft when it was shot down over Luhansk in eastern Ukraine.

He was not the oldest person in our count of the dead.

Mikhail Shuvalov, a retired power plant worker, volunteered at the age of 71. Media reports say he was initially rejected, but eventually he went to the front line and was killed on 10 December.

A trustworthy record

This count began because BBC Russian staff knew that otherwise there might never be a trustworthy record of fatalities.

Each side in a war downplays its losses. But Russia has a history of obscuring its wartime deaths far beyond what is necessary for military secrecy or the nation’s morale.

Years after the Afghan and Chechen wars ended, veterans and relatives are still struggling to get accurate public records of the dead.

Even the full extent of World War Two deaths is unacknowledged.

Working with Mediazona and members of the Russian public sending tips, the BBC collated and verified deaths mentioned by local officials, in media reports or from relatives on social media.

They monitored war memorials across the country for new names, and volunteers took photographs of new graves, putting a name and an identity to each confirmed death.

Seven new cemeteries for dead fighters recruited to Wagner units - six in Russia and one in Luhansk in eastern Ukraine - were uncovered during the course of the count.

The BBC contacted the Russian government for comment, but it has not responded.

November 2021

April 2023

Not all of Russia’s deaths are captured by our count - we can only pick up people mentioned in open sources, or on memorials and in cemeteries visited by volunteers. But the volunteers cannot cover all of Russia’s vast expanse.

And the count does not include the Russian-speaking separatists in the Donbas.

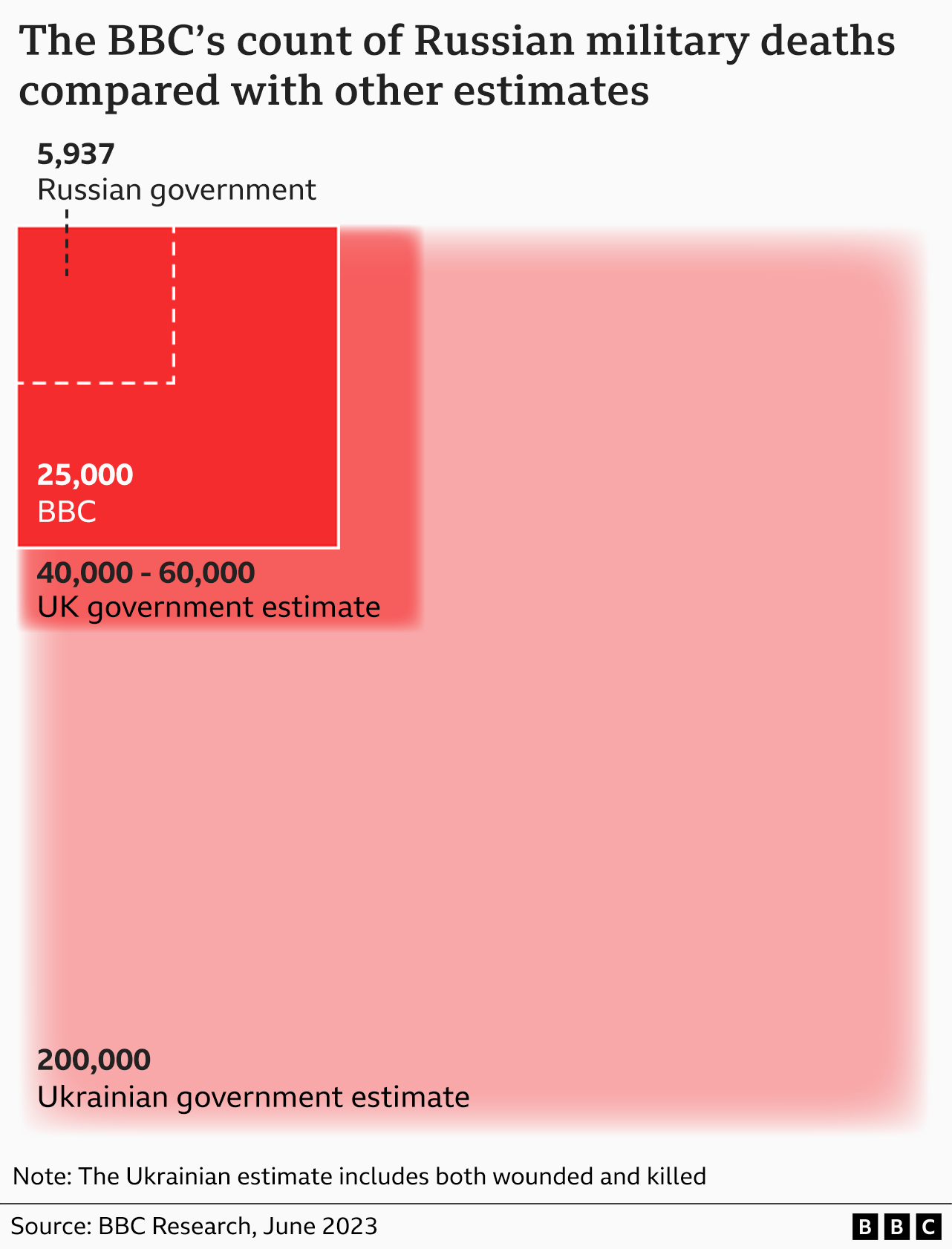

In February, UK intelligence services estimated 40,000 to 60,000 troops had been killed.

The Ukrainian Ministry of Defence estimates there are more than 200,000 Russian casualties - but this also includes the wounded.

All of these figures dwarf the Russian claim of about 6,000.

In February, UK intelligence services estimated 40,000 to 60,000 troops had been killed.

The Ukrainian Ministry of Defence estimates there are more than 200,000 Russian casualties - but this also includes the wounded.

All of these figures dwarf the Russian claim of about 6,000.

But incomplete as it is, the count has been able to provide answers for some bereaved relatives, where officials could not.

Anna's story

When the BBC contacted Anna - not her real name - in December, she only had suspicions about what had happened to Fail Nabiev, her former partner and the father of her daughter.

“Could you tell me what happened?” she said. “I don't know where he is buried or how he died.”

Nabiev’s grave was found in Bakinskaya, the cemetery seen in satellite photos above, and his identity was traced by the BBC.

Fail Nabiev's grave is in Bakinskaya cemetery | BBC

He had died on 6 October last year aged 60, in heavy fighting on the approach to Bakhmut - where all of Wagner’s forces were engaged at the time.

Anna, who lives in a region just north-east of Moscow, said she remained friends with Nabiev after they had split up: “He was a good person.”

But she said he was poor and in need of easy money, so he used to break into garages and steal car parts and other machinery to sell them. That was how he ended up in prison, where he was recruited by Wagner.

Confirming the deaths of prisoners in units run by Russia’s mercenary Wagner group can be especially hard. When Anna went to her local military recruitment office, they said there was no record of Nabiev.

As well as the uncertainty, the absence of official confirmation about a wartime death can also make it hard to claim the wages or compensation due to the family.

“I wanted to know if he was alive or dead. After all, except for your words, I have no information,” Anna told the BBC. “I would like to receive his medals, at least some kind of memory - this person is dear to me.”

BBC

‘25 million reserves’

Russia believes if it can just dig in and hold on, Western support for Ukraine will eventually fracture, says Dr Jack Watling, the Rusi land war expert.

If Ukraine can break through Russia’s fortifications in its long-planned counter-offensive, the depleted, inexperienced troops may suffer a “significant collapse”, he says.

But whatever happens, Dr Watling says Russia is unlikely to run out of manpower, citing defence minister Sergei Shoigu on the country’s mobilisation of civilians. “When he says, ‘I have 25 million reserves’, he is not joking. He's quite serious about the intent.”

That means messages to BBC staff counting the Russian dead will continue to arrive, from women such as Vera in Irkutsk, who has been trying for months to find out what happened to her brother, after rumours of his death in a Wagner unit.

“We don't know where to run, where to look for help,” she says. “We’ve had a disaster, how do we get to the truth?”

What weapons are being supplied to Ukraine?

What weapons are being supplied to Ukraine?

Ukraine in maps

Ukraine in maps

Satellite images reveal Russian defences before major assault

Satellite images reveal Russian defences before major assault