El Salvador's secretive mega-jail

Angelica already had a hunch where her missing husband, Darwin, was. But official footage, shared by the government and uploaded on to social media, confirmed her suspicions.

Painstakingly scrolling through it, frame by frame, she spotted him 25 minutes into the footage, shaking hands with his cellmate. She pressed pause, rewound, and examined the footage again.

Though his head was shaved, and he was wearing nothing except regulation white shorts, she had no doubt that this person was Darwin, whom she had not seen since his arrest 11 months previously.

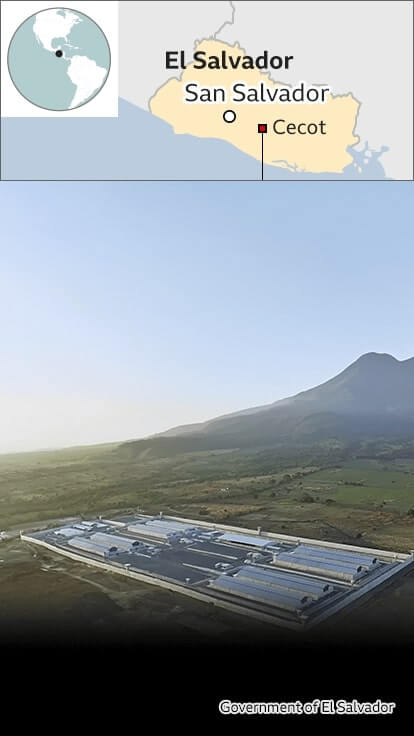

This was her first evidence that he had been transferred to El Salvador’s notorious mega-jail, Center for the Confinement of Terrorism (Cecot), which was opened in January by the country’s president, Nayib Bukele, in Tecoluca, 74km (46 miles) south-east of the capital San Salvador.

Cecot has become a symbol of President Bukele’s notorious "war against gangs", which the country’s ministry of security says has resulted in the detention of at least 68,000 people since the campaign began in March 2022.

There are thousands of Salvadorans who have not heard from their detained relatives for months, and who, like Angelica, look for them in videos, photographs, or - in the case of those whose loved ones are in lower security jails - by peeking through small holes in prison walls.

But President Bukele’s state of emergency, in a country which had become one of the most violent in the world, is very popular domestically. In a CID Gallup poll of 1,200 citizens in January, 92% of those polled said they had a "favourable opinion" of their leader.

His approval is largely fuelled by the drastic drop in recorded murders since his administration took office. Many Salvadorans stress this change, especially in neighbourhoods previously controlled by gangs which sought to intimidate the local population with the motto: "See, hear, shut up". Now residents can cross gang borders without harassment or fear of retaliation.

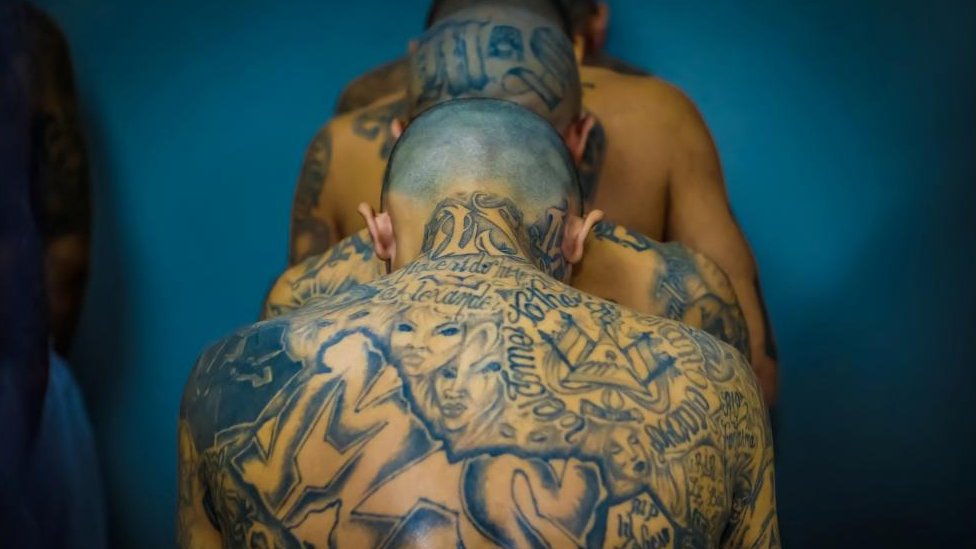

El Salvador’s government says Cecot can hold up to 40,000 prisoners who will exclusively be high-ranking members of two rival gangs - Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13) and Barrio 18 - whose warfare led to decades of terror and bloodshed in El Salvador.

The BBC has been repeatedly denied access to Cecot, but has recreated details of the jail using videos and photos shared by the government, and media outlets who were given access to the prison before it opened; interviews with Salvadoran officials; and documents shared with us by an engineer - on condition of anonymity - who was involved in the prison’s construction.

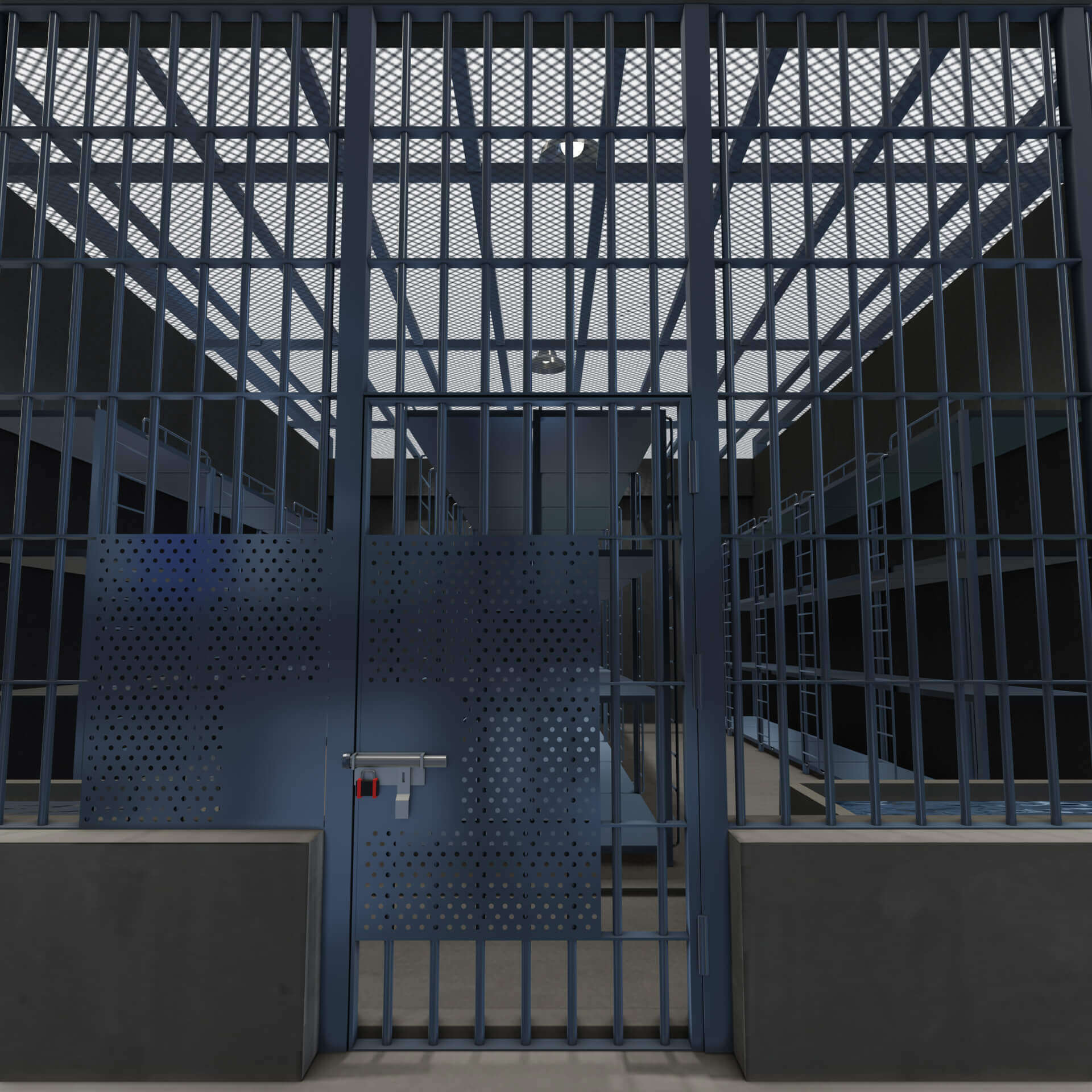

Cecot has 256 cells.

At its capacity of 40,000 prisoners each cell can house 156 prisoners if no new blocks are built.

The bunks are simply a metal plate with no mattress.

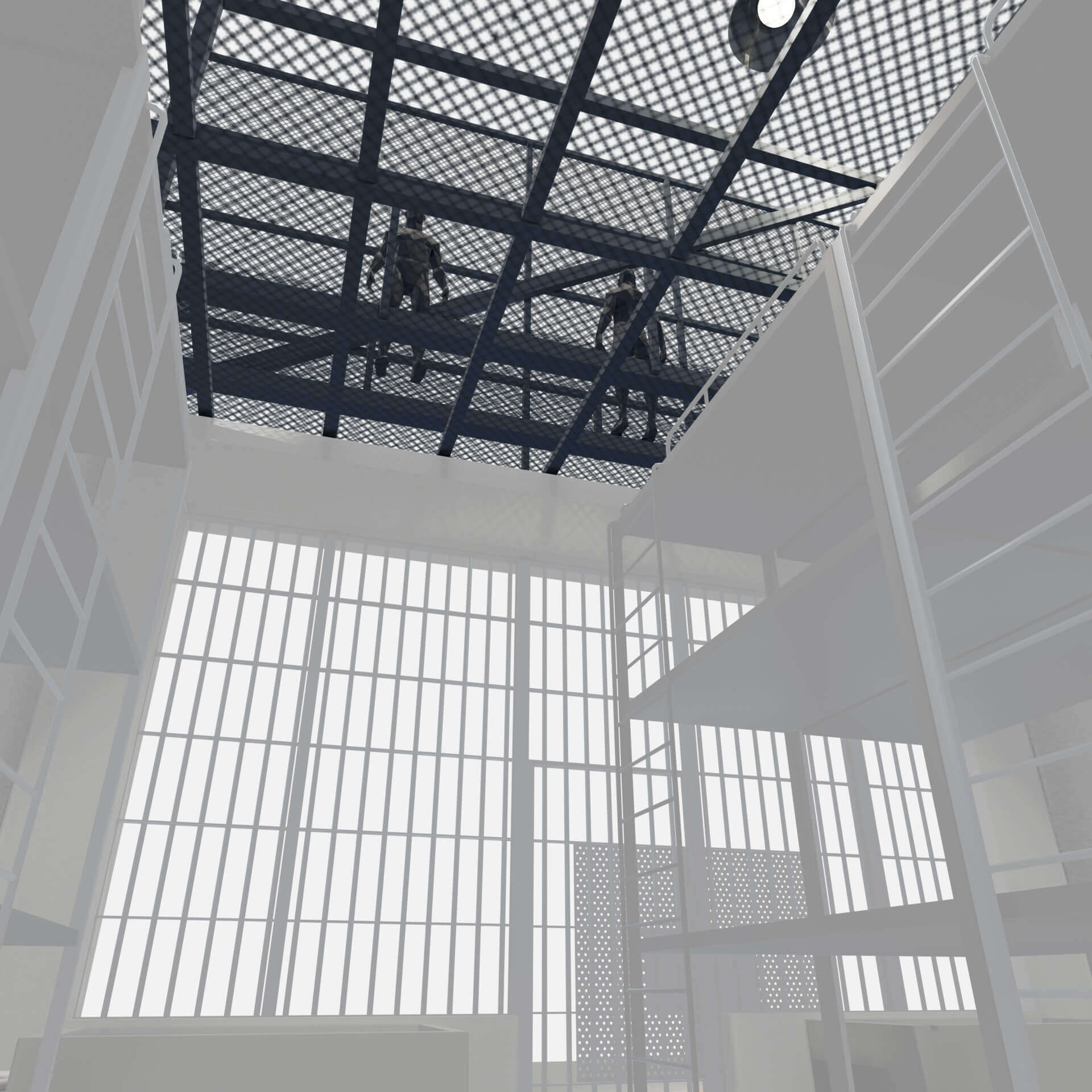

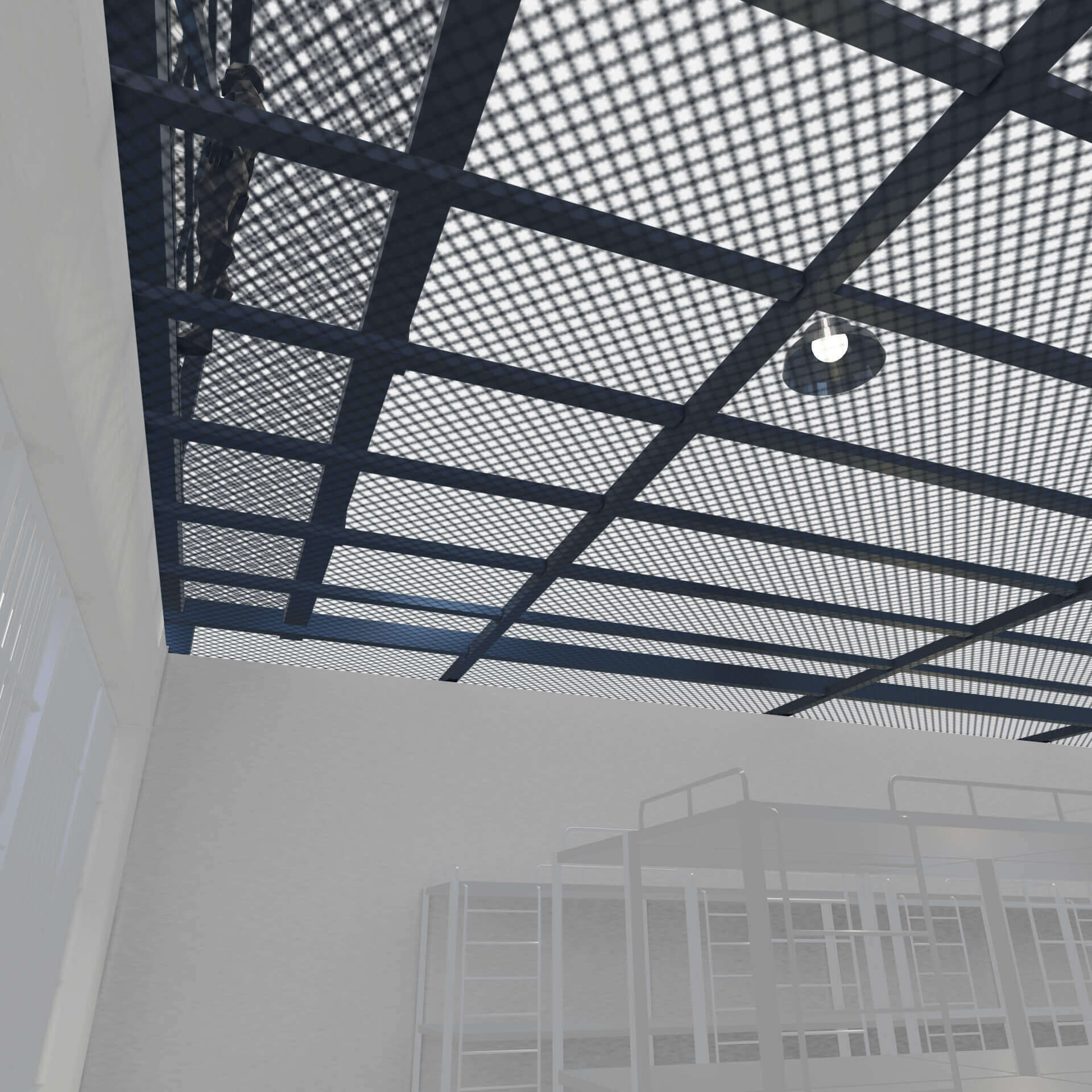

The ceiling is a diamond shaped mesh - the holes allow guards to keep an eye on the prisoners, and the lattice is made of sharpened metal to prevent prisoners hanging from it.

Each cell has two basins for prisoners to wash their clothes and themselves and two toilets which lack any privacy.

There are no windows, fans or air conditioners despite warm temperatures and high humidity all year round.

The authorities say prisoners will only leave their cells for online hearings or solitary confinement.

The space that each prisoner will have in their shared cell remains one of the big unknowns. Plans seen by BBC Mundo indicate each cell is 7.4m x 12.3m, or 91.02sq m - at capacity this would give each person 0.58sq m of space. The Red Cross recommends 3.4sq m per prisoner in a shared cell as an international standard.

El Salvador’s authorities have stated that they do not expect Cecot’s prisoners to ever be released.

It is not clear exactly how many prisoners are currently being held in Cecot. The authorities have only publicly announced two transfers so far - each of 2,000 inmates.

There is no outside recreational space, and no family visits allowed, the authorities say. This contravenes international guidelines on prisoner rights.

The criteria for incarceration in Cecot has not been made public, and it is not clear whether prisoners have been newly detained or transferred from other jails.

Little is known about how inmates are fed or looked after. No plans or photos have been shared of kitchen, dining room, shop or infirmary facilities.

The authorities say Cecot has state of the art security - entry scanning systems, a vast surveillance network, and a well-equipped weapons room.

The prison "is a concrete and steel pit where there is a perverse calculation to dispose of people without formally applying the death penalty", Miguel Sarre, a former member of the United Nations Subcommittee for the Prevention of Torture, told the BBC.

Antonio Durán, a senior judge in the city of Zacatecoluca, and one of the few magistrates openly critical of President Bukele’s emergency regime, agrees.

"In a state operating under the rule of law, the deprivation of liberty is the punishment. The offender is punished by depriving him of his freedom," he says.

"But here it is understood that he is deprived of liberty to be punished inside the prison. And that is not only wrong but also criminal. It's torture."

Cecot is seen by El Salvador’s government as the end of the line for its inmates.

"We have a commitment with the Salvadorans that (Cecot prisoners) will never return to the communities. And we are going to ensure we build the necessary cases (against them) to make sure they never return," Minister of Justice and Public Security Gustavo Villatoro told the BBC’s Will Grant in May.

"For us, Cecot represents the biggest monument to justice we have ever built. We don’t have anything to hide," he added.

A comment from President Bukele in May seemed to double down on this commitment.

"Let all the 'human rights' NGOs know that we are going to wipe out these bloody murderers and their collaborators, we will put them in prison and they will never get out," he tweeted.

It is not known how many - if any - of Cecot’s inmates have yet been formally convicted of the crimes they are accused of.

The BBC asked El Salvador’s government to give details of who is in the jail and on what basis, how it will accommodate 40,0000 people, and why prisoners’ relatives have not been given confirmation of their transfer, but did not receive any response.

A few weeks ago, the BBC got as close as it could to the jail.

"Not even El Chapo could escape from there," a police officer stationed in the area told us, referring to the notorious jailed Mexican drugs lord, who has previously mounted several improbable prison escapes.

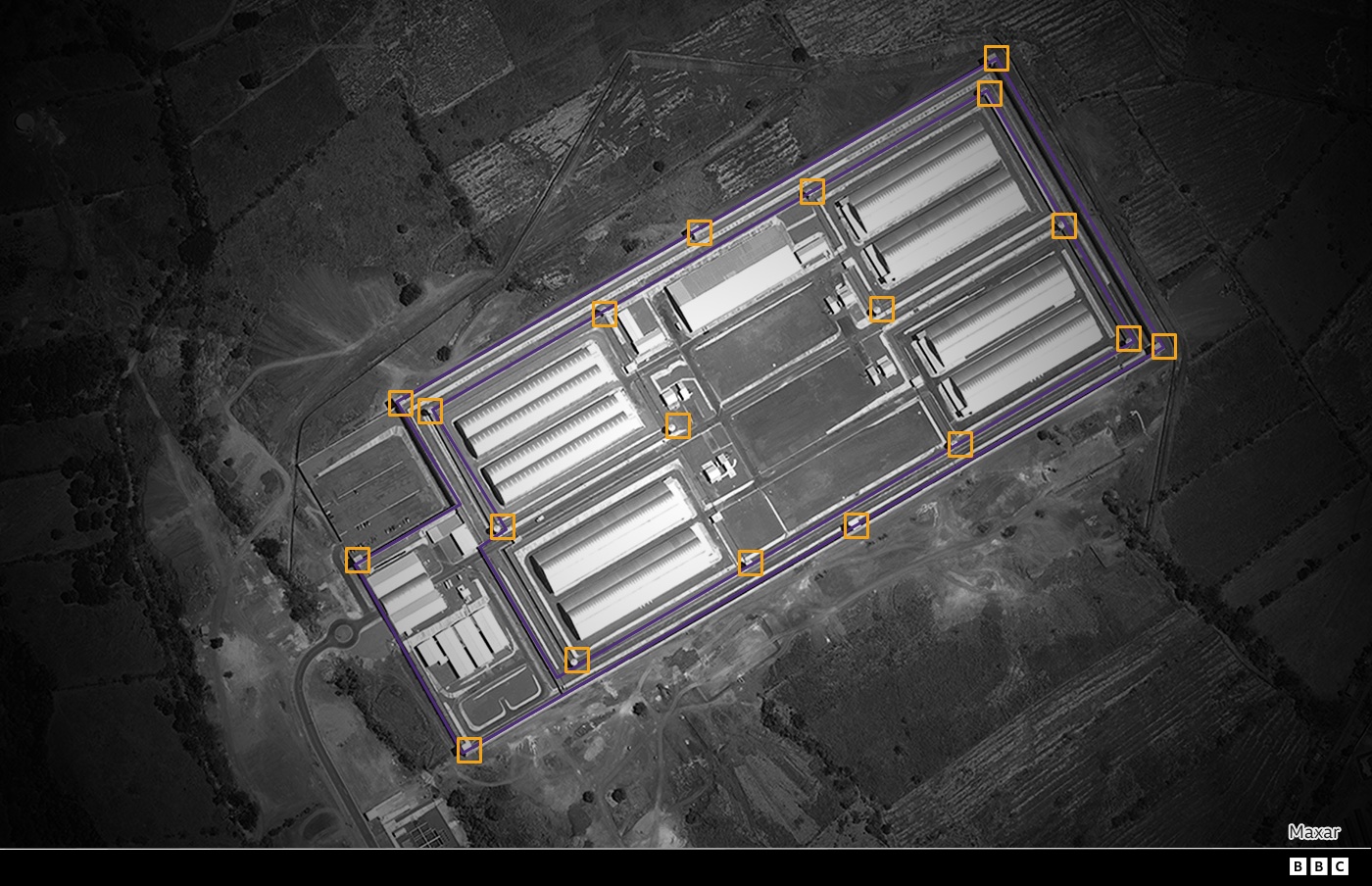

The prison complex is about 23 hectares (57 acres).

It has eight blocks with 32 cells each.

The are two sets of mesh perimeter fences which are fully electrified, and two reinforced concrete walls surround the facilities. The perimeter of the outer wall is 2.1km (1.3 miles). And there are 19 watchtowers.

The policeman admitted that his life had improved considerably in recent months.

"Before, my time was spent extricating gang members from their homes, with all the risk that that suggests. Now I spend the day at checkpoints, and occasionally even have time for a coffee."

Residents of neighbourhoods previously controlled by the gangs seem particularly supportive of President Bukele’s policy.

"This place was not safe at all until the president did that," Dennise, who lives in La Campanera, on the outskirts of San Salvador, told the BBC.

"I think the (emergency) regime was the best decision that could have been made and that this is the best president we have ever had."

Her mood contrasts with that of Maria, 23, whom we meet not far from Cecot, in her house in El Maniadero. Her mother’s partner worked for six months on the construction of the prison, before being arrested himself for "unlawful association".

Maria no longer risks going out much, she says. Her friend Jessica - mother to a three-year-old girl - has also been taken away by the police under the emergency regime.

"It seems that being young is now a crime in El Salvador," Maria says.

The BBC spoke to dozens of relatives of prisoners detained under the so-called "state of exception" regime, who all gave a similar account.

They said their loved ones were taken from their homes - without being shown a search or arrest warrant - to detention centres or jails, and then subjected to group online hearings along with dozens of other detainees. In those hearings the judge would order a pre-trial detention, while the prosecutor's office investigated whether there was evidence for a formal charge - a process that can last for months, even years.

Outside Ilopango prison in San Salvador

A report in May by Cristosal, El Salvador’s primary human rights NGO, concluded that in the first year of these measures, dozens of inmates died from torture, beatings or lack of healthcare in the country’s other prisons.

The government has not publicly responded to the report. But the country’s human rights commissioner Andrés Guzmán Caballero, who took office on 24 May, conceded during a media event that month that the report was "worrying".

"When the prison population is made up of two or three gangs, or three groups, that have clashed a lot with each other, it can have consequences such as increased deaths - the causes must be reviewed on a case by case basis," he said.

Cecot, Cristosal says, is a particular worry because it is so difficult to monitor.

"Conditions at Cecot might become inhumane and degrading because no-one has access to that prison," says Zaira Navas, El Salvador’s former police inspector general who is now Cristosal’s legal lead.

"No lawyers, no ombudsman, not even the media can enter and verify the conditions inside."

As for Angelica, who had spotted her husband in the Cecot footage, she told us that she was now planning to get any information she could about his situation.

"There is no other way but to keep ploughing on… my children and husband need me to do that."

Thousands of tattooed inmates pictured in El Salvador mega-prison

Thousands of tattooed inmates pictured in El Salvador mega-prison

El Salvador: The people caught up in the gang crackdown

El Salvador: The people caught up in the gang crackdown

Mass arrests bring calm but at what price?

Mass arrests bring calm but at what price?