Dr Cool

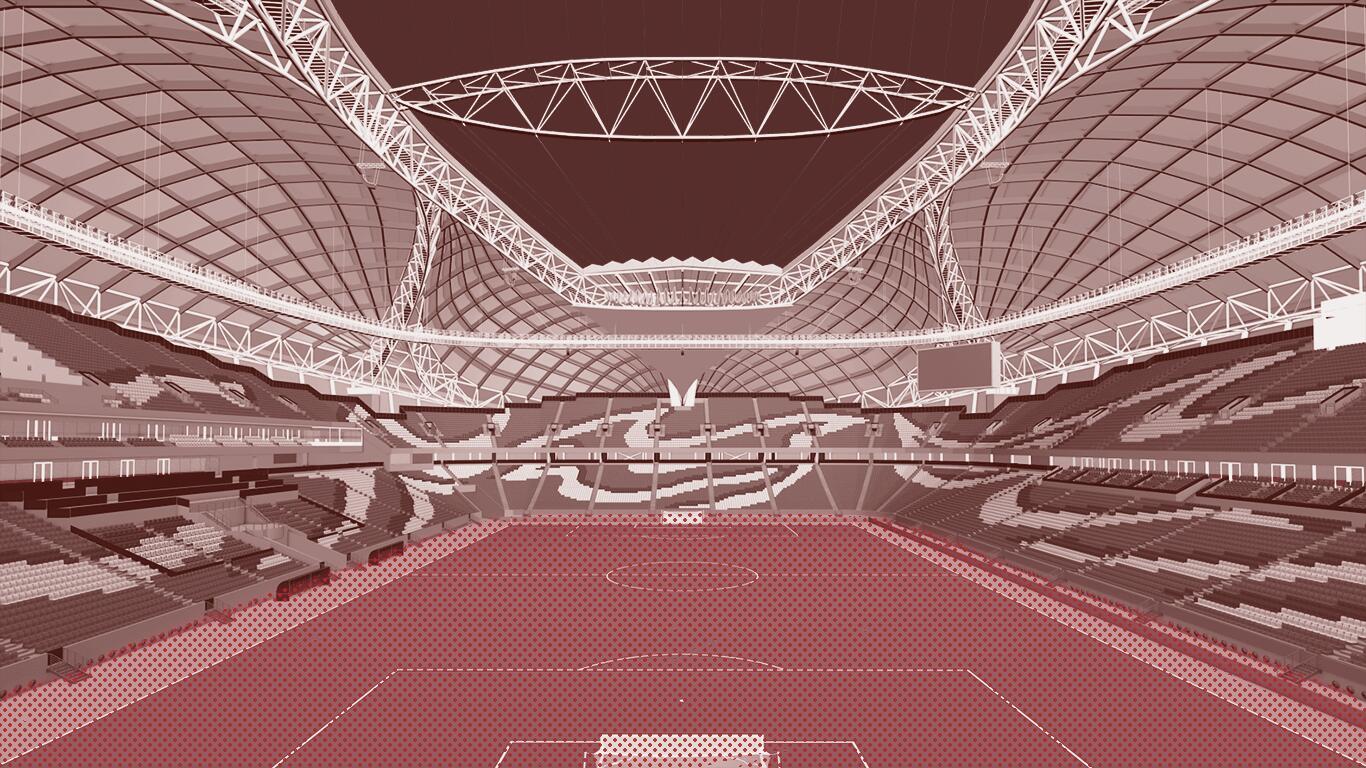

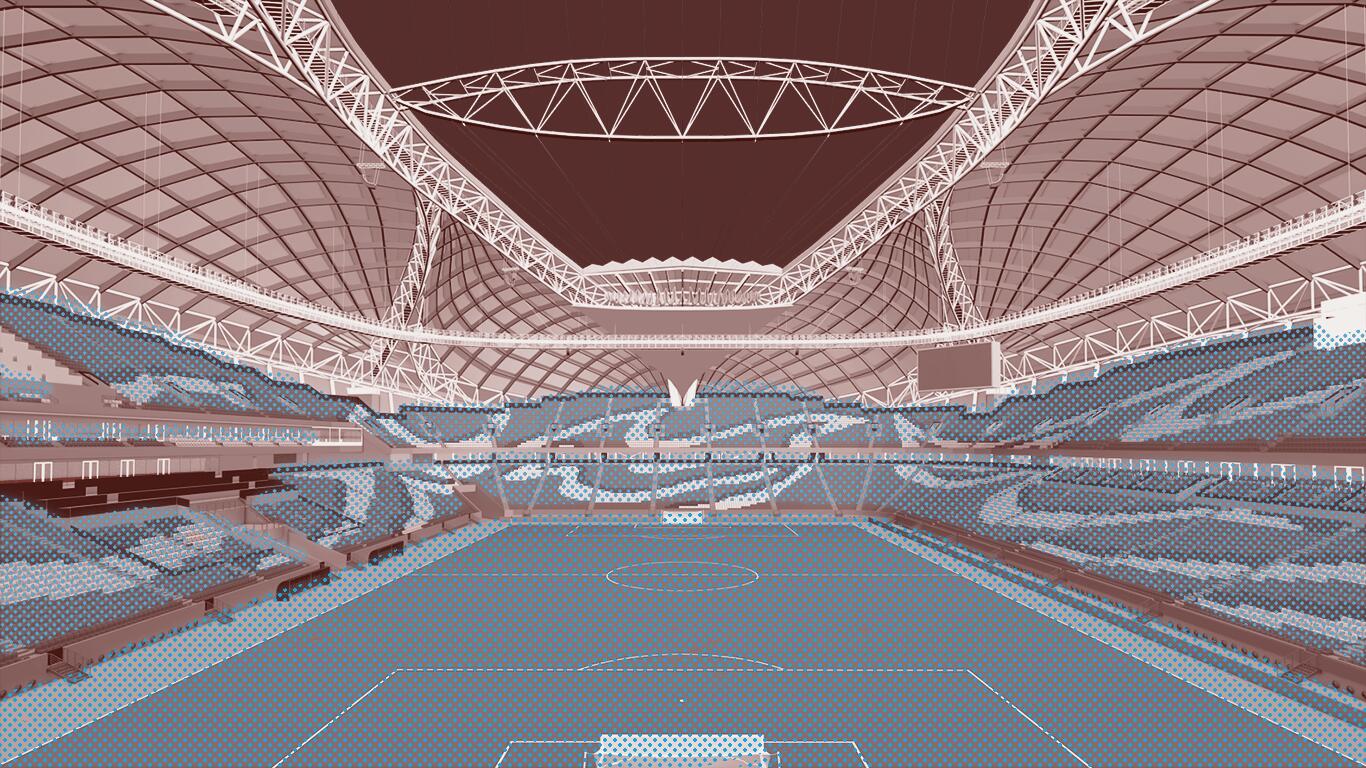

The man who devised the entire system, Dr Saud Abdul Ghani, told the BBC that Qatar wants to create a legacy, to serve the country long after the footballers have gone home.

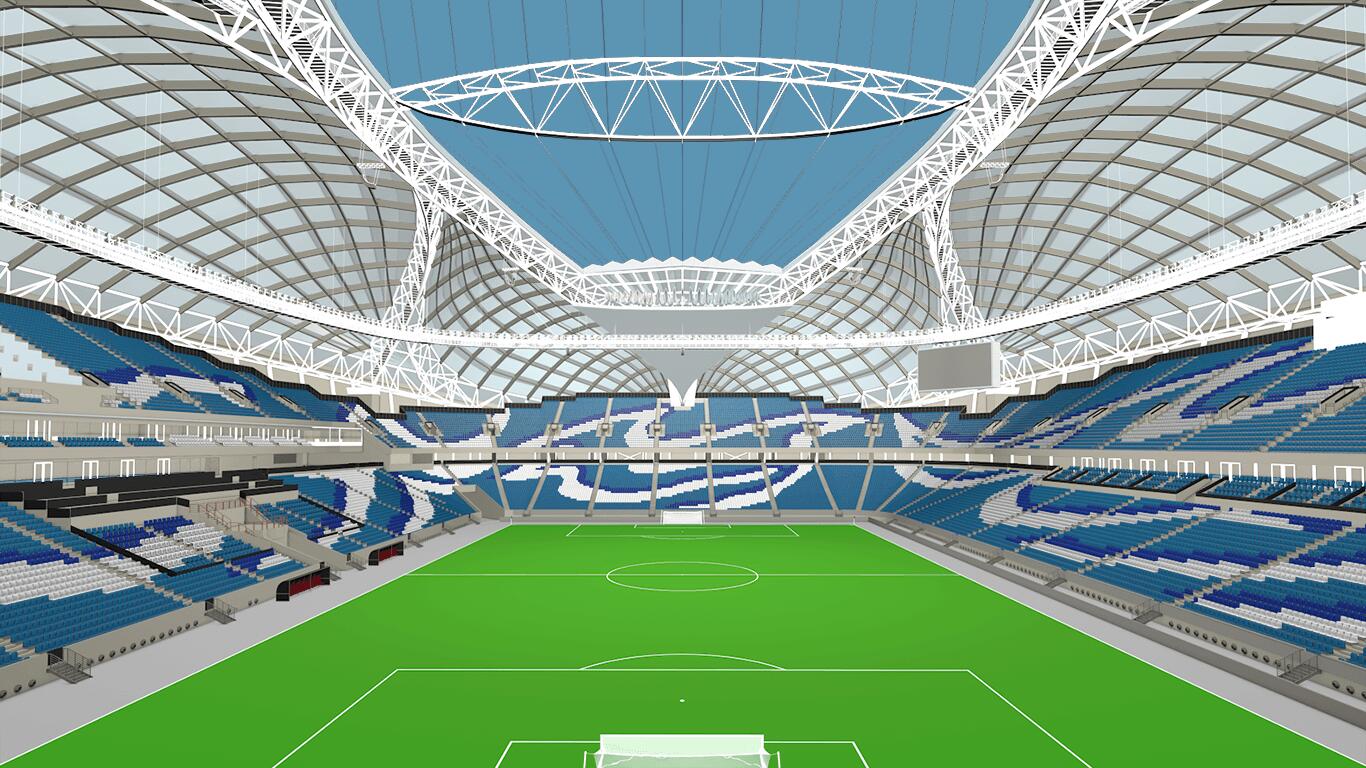

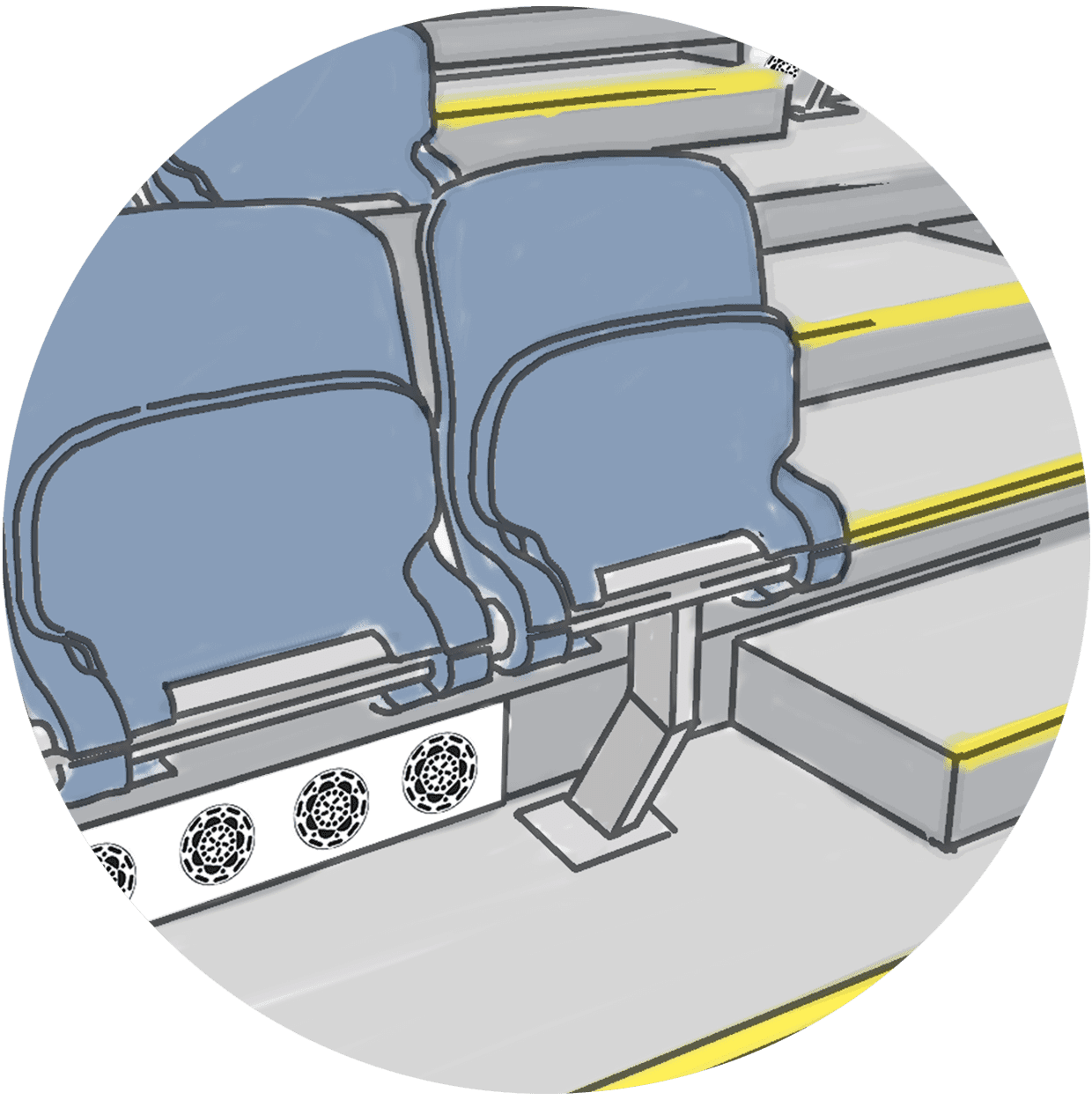

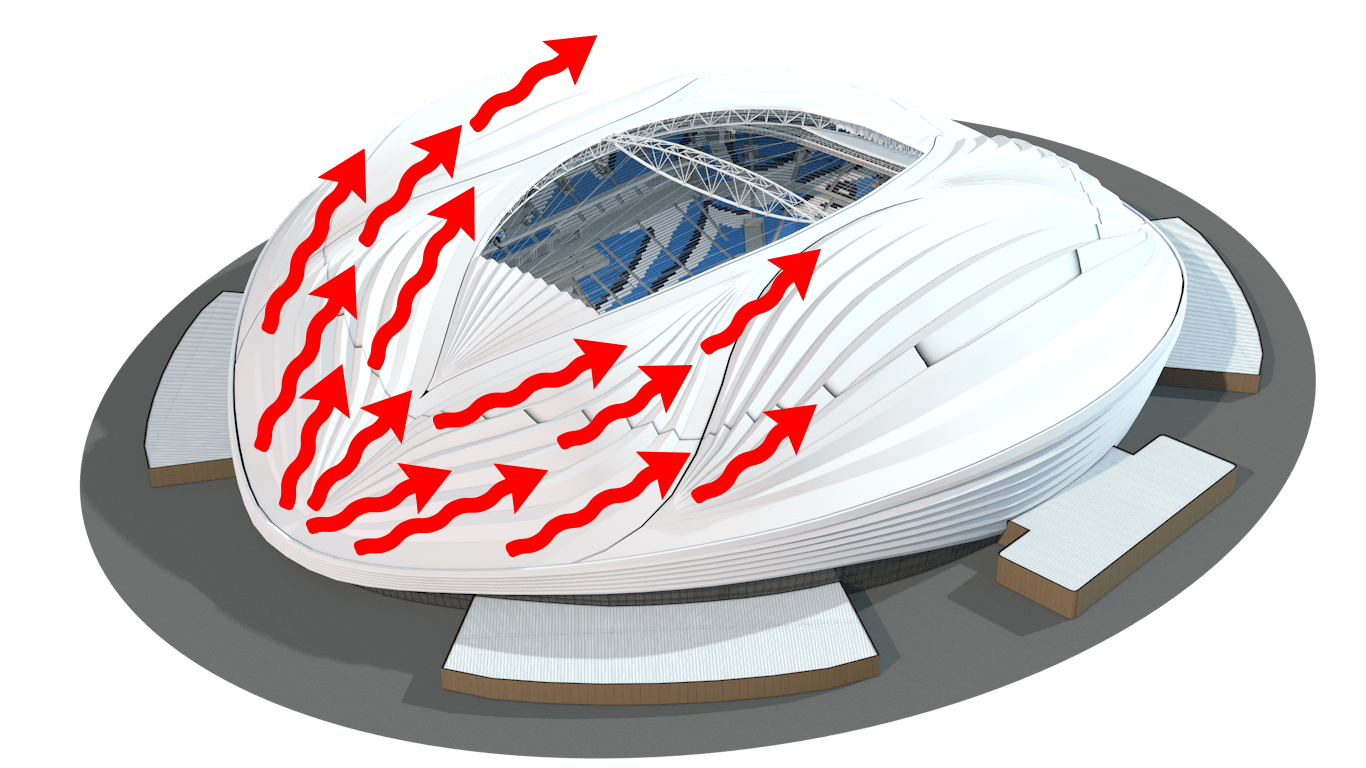

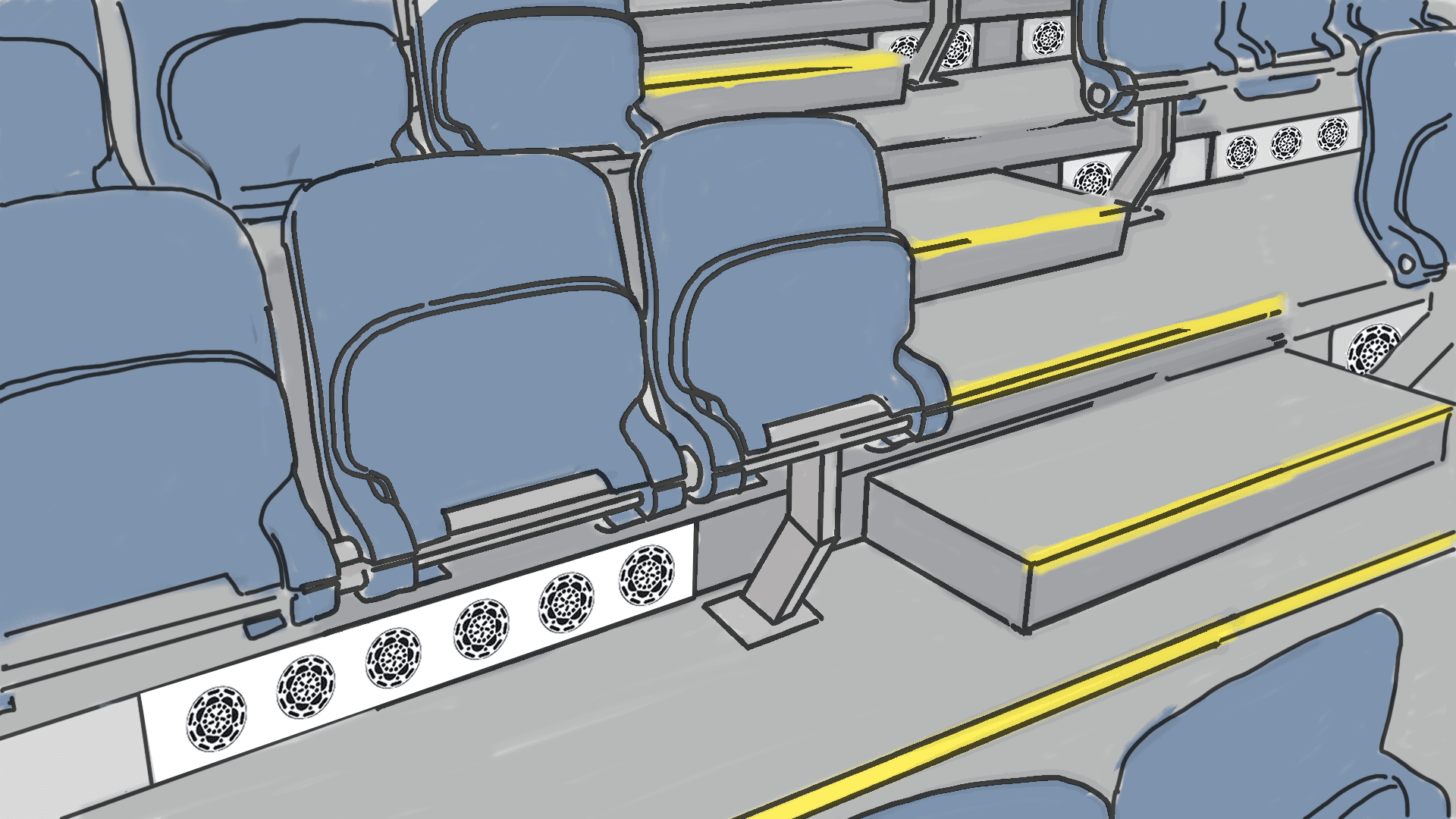

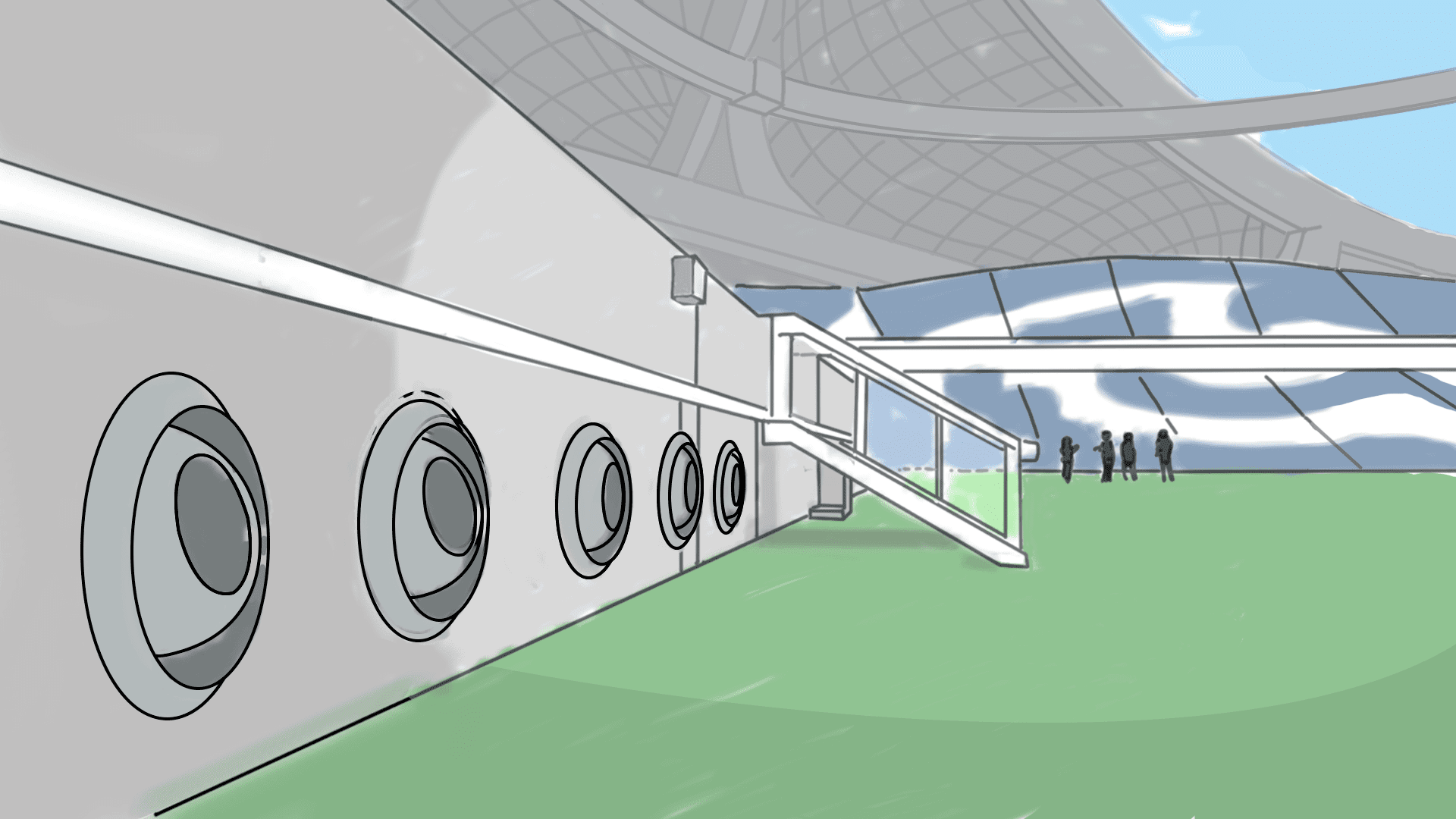

He says years of extensive research have gone into what he calls "thermal comfort", creating an environment that is pleasant for the maximum number of people. Conversations with athletes and fans at the World Athletics Championships, held in Qatar in 2019, helped inform the design that will benefit the visitors and players in the World Cup.

A player's perspective

The BBC reached out to Hajar Saleh, a defender with Qatar's national women's football team and a player since she was 11. She knows all about the demands of playing top level sport in extreme conditions. She says humidity is the biggest challenge.

We are used to heat, but when you combine heat and humidity things become more difficult Hajar Saleh

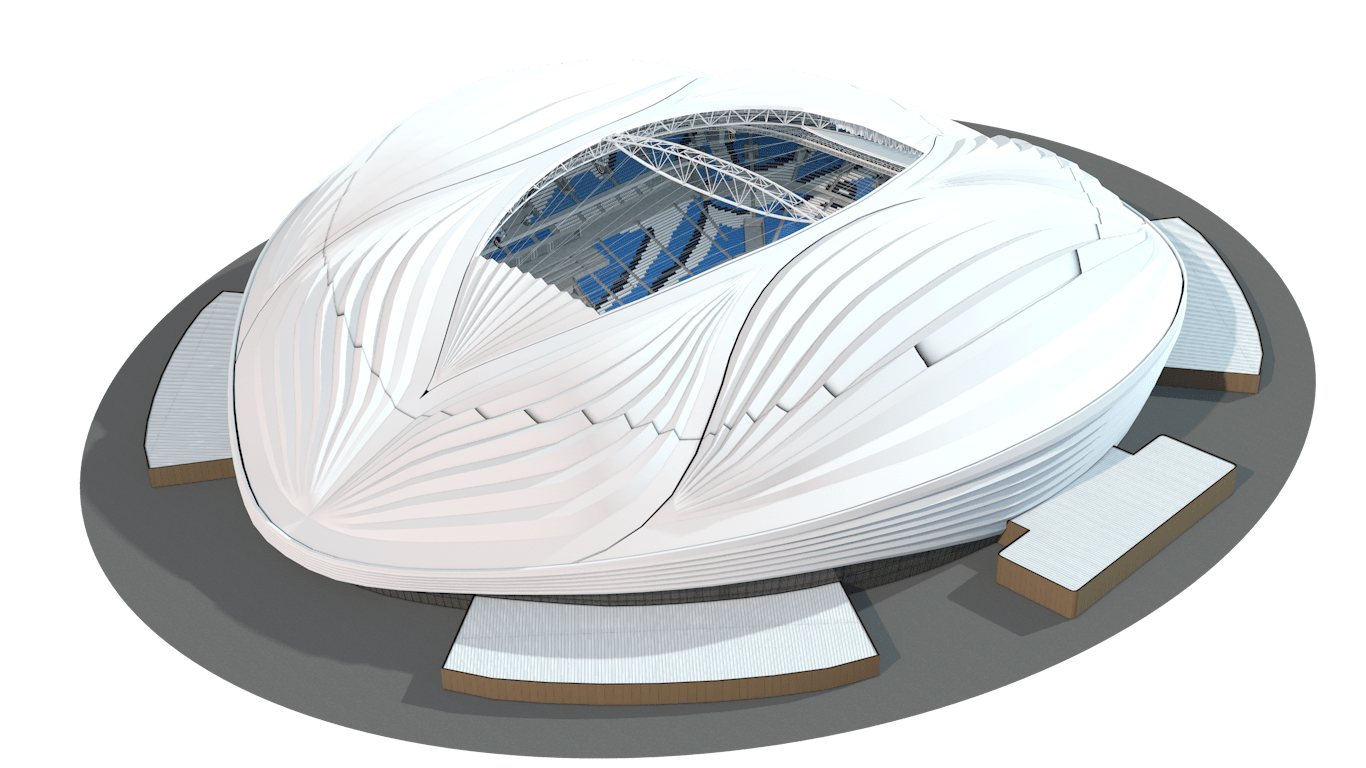

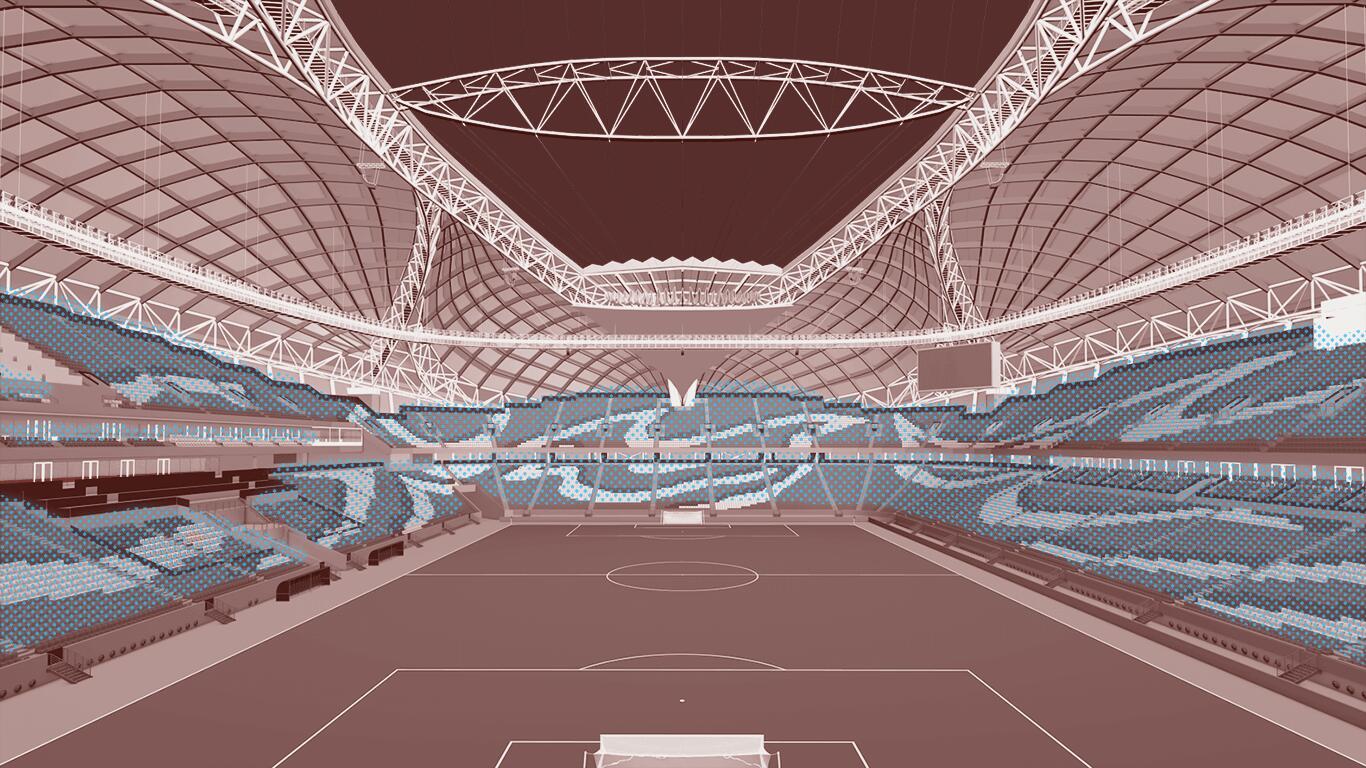

Hajar has had first-hand experience of playing in two of the new venues with the new air conditioning systems, the Khalifa and the Educational City stadium.

She says it makes a huge difference, especially when playing in June, one of Qatar's hottest months of the year.

Is the system sustainable?

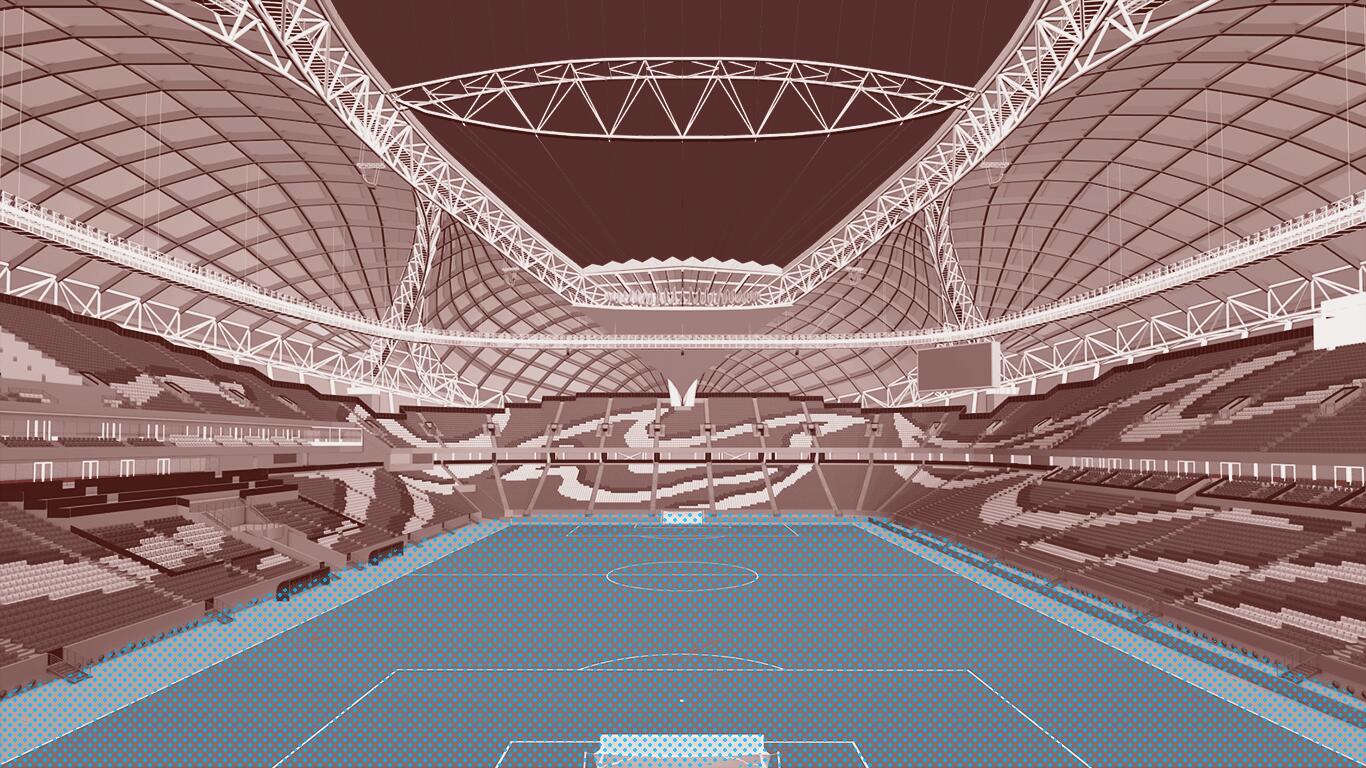

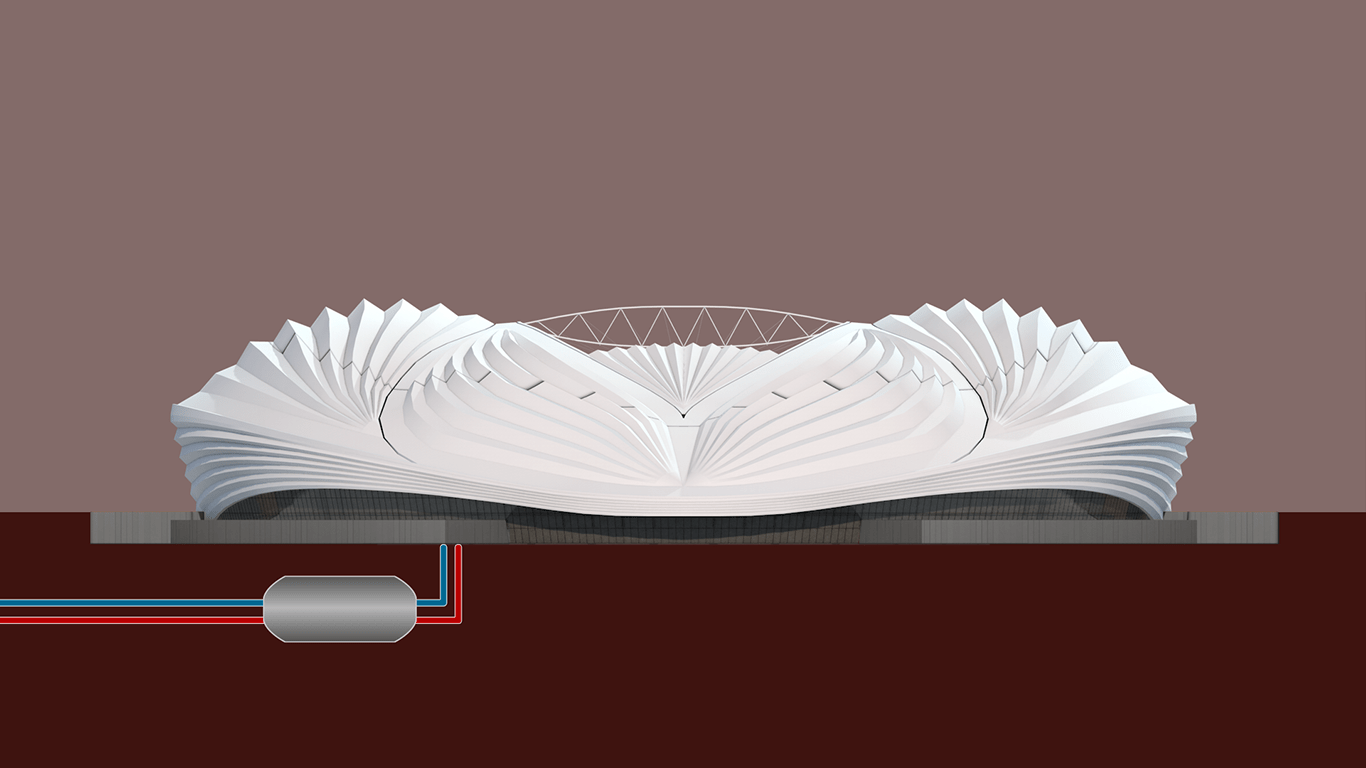

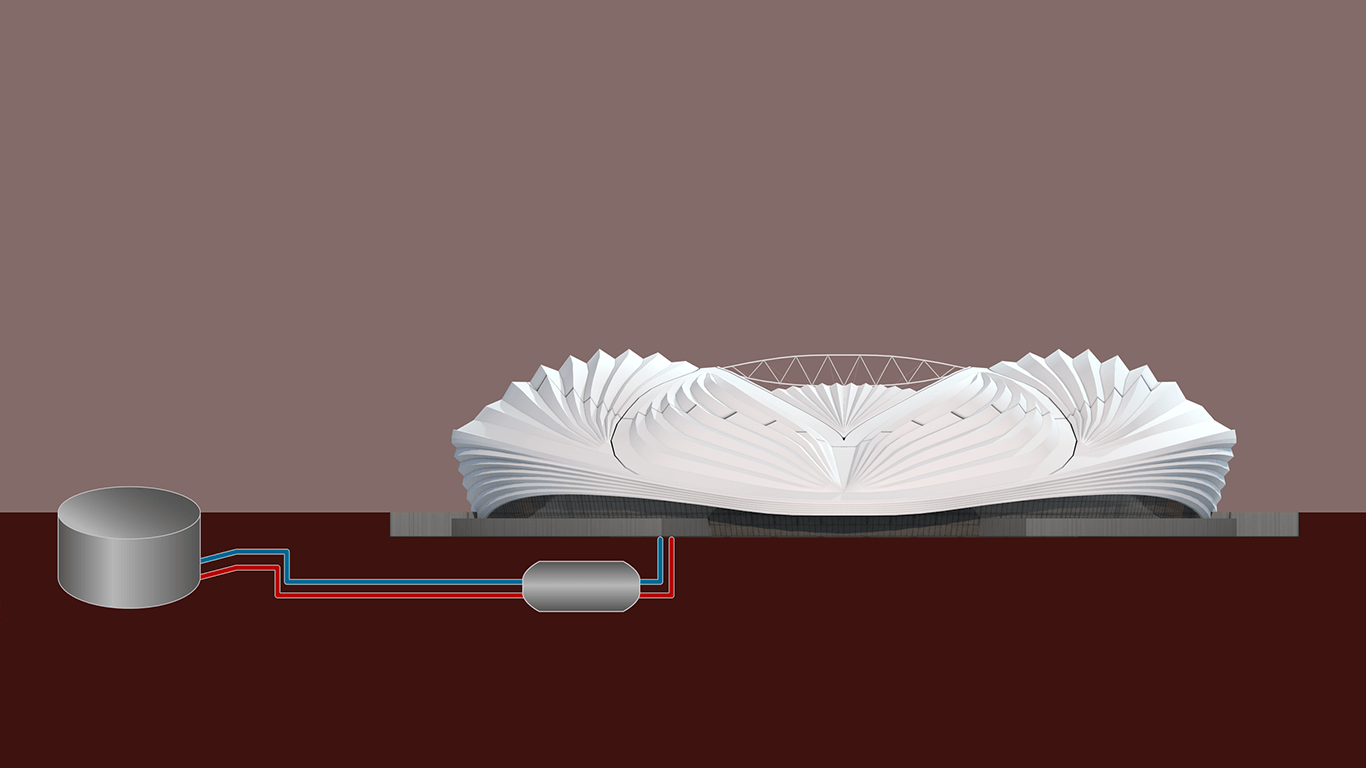

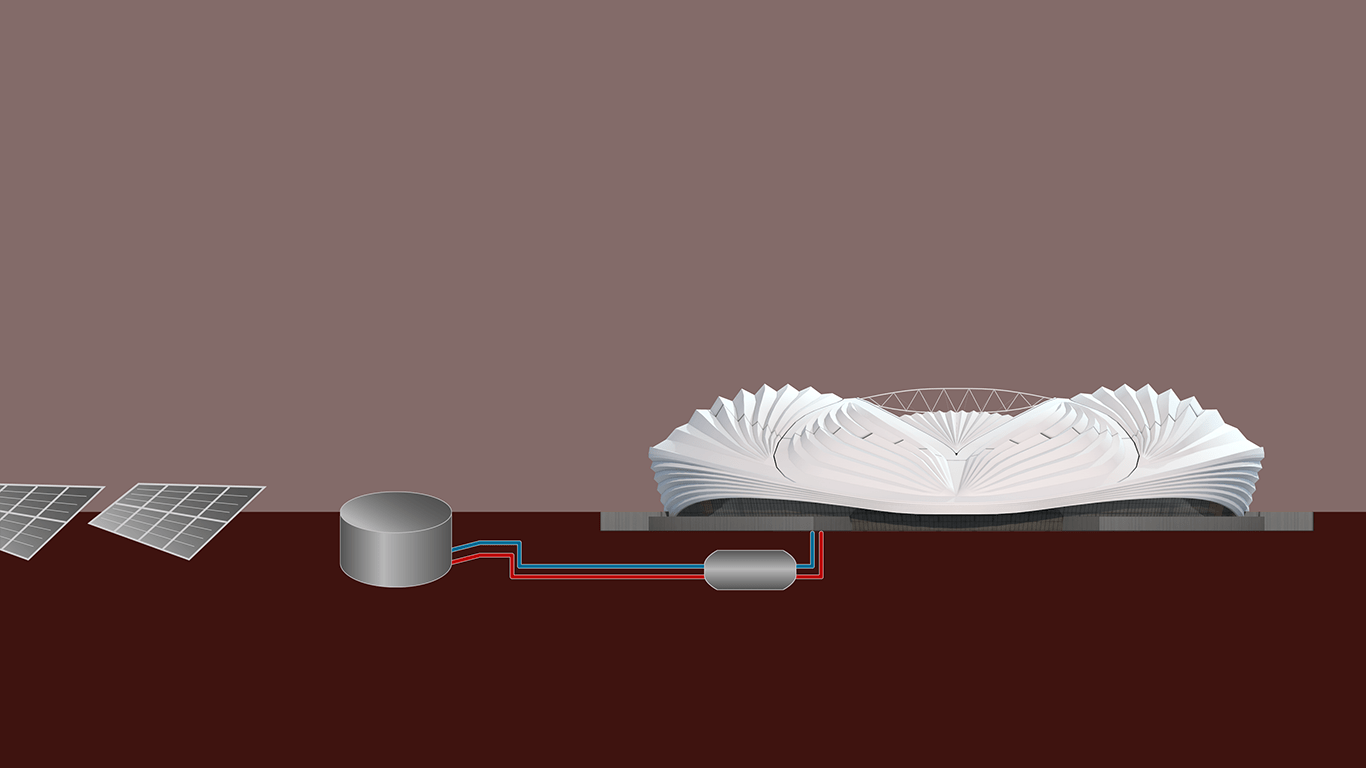

The organisers of Qatar 2022 promise that the power for cooling entire stadiums will not result in additional greenhouse gas emissions, because the electricity comes from its new solar power facility.

But the aim of ensuring the entire tournament is carbon neutral is a much bolder ambition.

The amount of "embodied" carbon - that's the emissions produced while building the stadiums - accounts for 90% of the venues' overall carbon footprint, with an estimated 800,000 tonnes of greenhouse gases released into the atmosphere. That's the equivalent of driving a passenger car around the world 80,000 times, according to the US Environmental Protection Agency emissions calculator.

Looking beyond the stadiums, there's the impact of transport to the World Cup, including flights taking fans to the country.

Fifa says that the compact nature of the tournament, with only short distances between venues means that emissions from travel between sites in Qatar is estimated to be less than a third of those produced at Russia 2018.

Qatar's green promises rest on using carbon offsetting to compensate for all the CO2 already emitted.

So far it's not very clear how they hope to achieve this. Fifa says it is using different technologies to compensate for World Cup emissions, including energy efficiency, waste management, renewable energy and, possibly, planting trees. However, the final selection of projects cannot yet be confirmed.

Such schemes can take decades before they become effective in capturing carbon. A recent BBC investigation suggested that some forests planted for offsetting only exist on paper.

So it will be some time before we can truly judge whether Qatar has indeed achieved its green goals or whether the claims of sustainability are a lot of hot air.

The country is also still fending off criticism for the high human cost among the 30,000 migrant labourers who built the stadiums, including a large number of workers killed and seriously injured. There have also been accusations of forced labour, gruelling working conditions, squalid housing, unpaid wages and passports confiscated.

The Qatari government disputes these accounts, and insists that since 2017 it introduced measures to protect migrant labourers from working in excessive heat, limit their working hours and improve conditions in workers' camps. However, in 2021 alone, 50 workers died and more than 500 others were seriously injured in Qatar among all those participating in projects connected with the World Cup, according to data gathered by the International Labour Organization. This is another off-field issue where the desert kingdom's record will remain under scrutiny.

World Cup 2022: How has Qatar treated stadium workers?

World Cup 2022: How has Qatar treated stadium workers?

Fifa World Cup Qatar 2022: Day-by-day guide to fixtures

Fifa World Cup Qatar 2022: Day-by-day guide to fixtures

How phantom forests are used for greenwashing

How phantom forests are used for greenwashing